I have a whole backlog of photos and videos of flora and fauna (from STL) that I am researching. Some are creatures I already know a good amount about, others…not so much. With my most recent post about cicadas, I decided the next post should be about one of the cicada’s mortal enemies. An insect that has specialized in killing cicadas and in fact relies upon them for its own survival. I am referring to Sphecius speciosus, more commonly called, and very accurately named, the cicada-killer.

On August 5th of this year, a good friend of mine, Chris Cox, sent me a screenshot of his Google search. He had apparently discovered that there are cicada killers in his yard, and stated (wrongfully) that they are his latest pest. Without missing a beat, I suggested he catch one as they are fascinating to look at. Despite my love of nature rubbing off on him, he never got up the nerve to catch one. As luck would have it, I had a personal day on the books for the following day to have some dad time with the kids. It was a scorcher that day, but we decided to walk down to Wilmore Park and explore. We hit the playground for a few, then we walked the trails looking for birds, bugs, or anything else that may be of interest. As we were walking these trails, sweating profusely, my daughter casually says to me…”uhm dad…DAD WHAT ARE THOSE!” pointing to a pair of massive hymenoptera locked in mid-air battle buzzing around us.

We all paused and watched as they split and flew over to the field right beside the trail. That’s when I noticed there was a swarm of these suckers, buzzing around feverishly and grappling over and over mid-air. There were tons of them, and as our eyes gazed off into the distance we realized that the festivities spanned as far as the eye could see. The whole field was buzzing, you could audibly hear them zipping around, their bright yellow and orangish bodies flashing by. We stood and watched for a few moments before I said excitedly “Cicada-killers!”. At this point my daughter seemed a tad bit nervous (despite my reassurance they won’t bother us) and my son announced that he was hot and ready to go home. Seizing the opportunity to get my net and get back for the sake of science, I was not going to put up an argument this time. I called the wife and asked if she would drive my net and a jar to the park, she was busy but said she would meet me there. With two tired children and a puppy eager for rest in tow, we ended up making the trek back to the house as she was bringing my bug-catching gear. Making a quick exchange in the house, and chugging a bottle of water, I mounted my trusty bike and pedaled like a kid chasing down the ice cream truck.

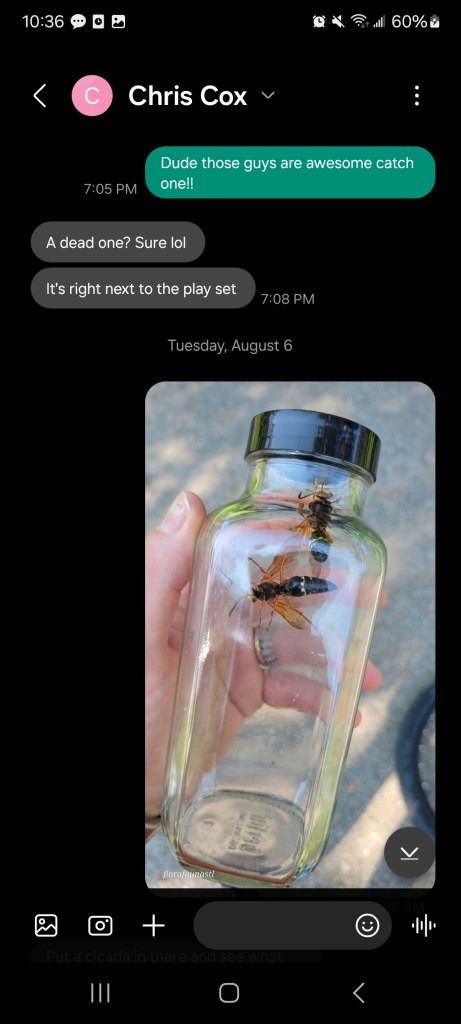

When I arrived the cicada-killer mating frenzy was still in full effect and I caught two in my net, got them into a jar, and immediately sent Coxy (Chris Cox) a picture. What are the odds, well, I mean they were relatively high because it is the time of year they mate and are out and about, but still, the fact that he brought it up first and within 24 hours I’ve procured specimens, I mean come on, that’s pretty cool! Anyway, that’s the story of how I captured them and boy was I excited. That’s enough about the adventure of the catch, let’s dive into some information about Missouri’s largest wasp.

Cicada-killer wasps emerge as adults during the dog-days of summer, ominously similar to the emergence of the annual cicadas. The males arrive at the scene first and start battling it out for prime breeding ground a few feet above the tunnels from which they emerged. As we witnessed, they lock onto each other mid-air and hold on until eventually breaking free from one another after an erratic flight. The males look as though they are stinging each other mid-air, but are actually incapable of stinging, not only each other but anything. The males lack stingers completely, but will still poke at offending parties with their abdomen. The males are very curious and will fly over to observe humans or any other creature in their vicinity. Their rapid flight and lack of shyness often leads to people feeling threatened, but again, there is nothing to fear as these guys are harmless.

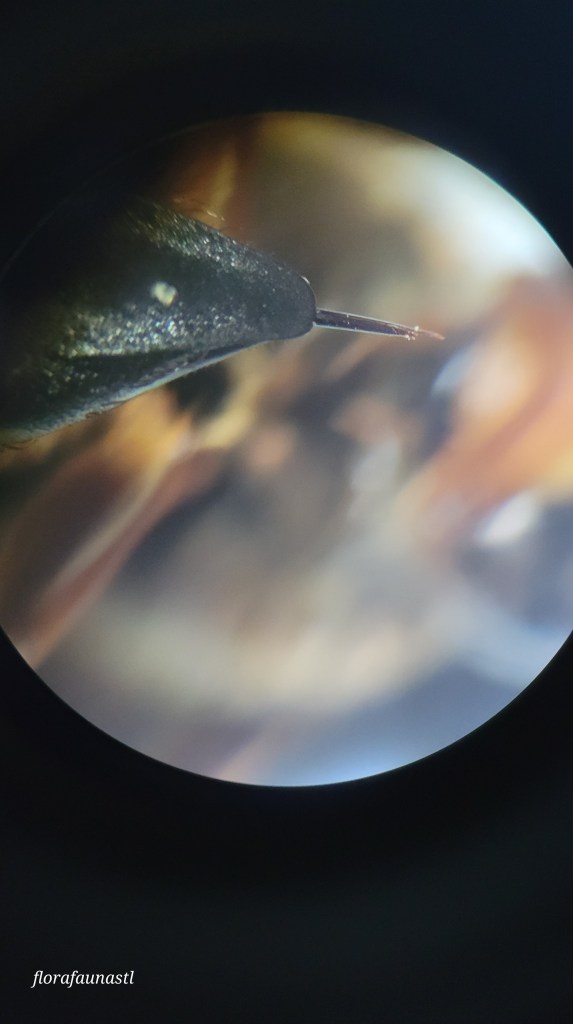

The females are a different story (kind of) and do possess stingers, although they are also only known to sting if they are provoked. Think aggressive handling or stepping on one of them barefoot. Other than being pushed to sting, the females are more likely to elude and avoid than attack. The fear of wasps in general is probably a solid fear for most people as it aids in your survival and or, at the very least, the avoidance of pain. But solitary wasps, which cicada-killers are, rarely sting, and for good reason. You see, certain types of hymenoptera (the order of insects that includes ants, bees, wasps, hornets, and sawflies) do live in hives but the vast majority live in solitude. The ones that live in hives work as a team, they all help to raise the colony and take care of each other. That said, they are more willing to attack and therefore risk their life because they know their offspring will be cared for by their sisters. Yellow jackets, for instance, build communal nests, so if one dies, the others will take care of her offspring, her genes will live on. For those hymenoptera that live solitary lifestyles, they do not have the luxury of knowing their young will be cared for if they die, so they are best suited to avoid conflict unless it is absolutely necessary.

I’ll admit their sheer size makes them look menacing, but you really only need to be concerned if you are a cicada. And even then they won’t kill you, well, the adults won’t at least because they feed on nectar. But the females, which are slightly larger than males and have the ability to sting must have those attributes for a reason right? But of course, you see they use those stingers to inject a neurotoxin into cicadas (typically female cicadas) which paralyzes them. And they are larger than the males because they then need to lug around said paralyzed cicada. Where are they taking the cicadas you ask? To their underground chamber of horrors, I mean nursery of course! Much like the golden digger wasp, cicada-killers bring fresh meat home for their babies. Cicada-killers dig tunnels that are roughly 1 to 2 feet deep but can span out 1 to several feet in multiple directions.

The tunnels will have multiple cells or chambers which will house the next generation. Once these underground nurseries have been built the cicada-killer mom will drag the paralyzed cicada into a cell, lay an egg on it and repeat several more times. The eggs will hatch in a few days and begin to chow down on that delicious and terrified cicada by burrowing into its body. It will consume and grow within the paralyzed cicada for a week or two and then emerge to build its cocoon made of silk and dirt, in which it will overwinter. In spring they pupate for about a month and emerge as adults in summer. Can you imagine!? This is real-world xenomorph/face-hugger action happening, in fact, the hit 1979 film Alien was inspired by parasitoid wasps, or at least that’s what I’ve heard. Cicada-killers are what is known as ectoparasitic, meaning they develop outside of their specific host, they are also idiobiont, meaning they sting and paralyze that said host. The female larvae are often given a few more cicadas to annihilate because they will need their strength to hunt, wrangle, sting, and carry cicadas for the next generation. The cicadas are often twice as heavy as the cicada-killers so moving them can be quite a chore. They will often drag the cicada up a tree to gain leverage and use the laws of physics to aid in their flight back to the nest. If they catch the cicada close enough or if no trees are around they will drag it back to the nest. Although cicada-killers are solitary wasps, they will sometimes share a main entrance to their nursery but each female will build her own separate chambers. Cicada-killer adults will die out in the fall when the temperatures begin to drop.

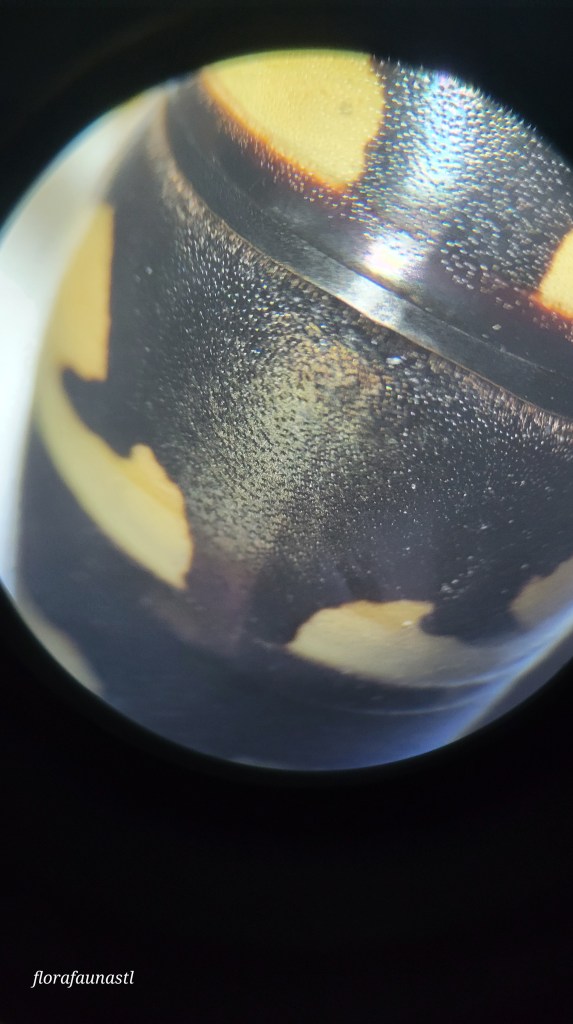

As you can see from the video, these wasps are huge reaching lengths of up to 2 inches. They are often misidentified as Asian giant hornets, yellow jackets, the European wasp, and the eastern stizus. Their markings are most similar to that of the eastern stizus but even an untrained eye can differentiate the two based on their markings, as the cicada-killer has hook-like patterns instead of stripes, although they are similar in coloration.

Eastern cicada-killers can be found east of the Rocky Mountains throughout the Midwest and eastern United States, down into Mexico and South America. Despite their gnarly lifecycle, they play an important role in our ecosystem by aiding in cicada population control, which in turn can help out plant and tree life, and their tunnels also help to irrigate land. As my friend stated, some people may find them to be pests. If they are in large numbers, I could potentially agree with this as their holes can be rather disruptive to a yard and their swarming around nests may put some people on edge. These have always been some of my favorite wasps as they are very colorful, large and non-aggressive, which makes catching and studying them a little less intense. They can be found in many environments but prefer areas with loose clay soil and an abundance of cicadas, which we have plenty of here in St. Louis. So next time you are out and about in the dog-days of summer keep an eye out and you may be lucky enough to see one of these ladies escorting a cicada to the dinner party, YUM!!!

References:

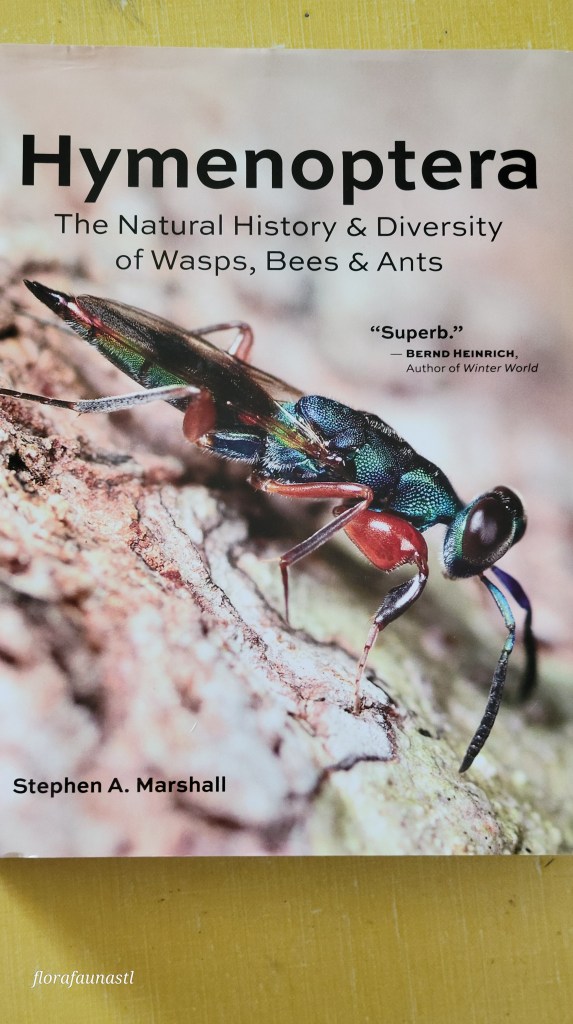

Marshall, A., Stephenson, (2023), Hymenoptera The Natural History & Diversity of Wasps, Bees & Ants, Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sphecius_speciosus

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/eastern-cicada-killer-wasp

Leave a reply to Cicadas – Flora Fauna STL Cancel reply