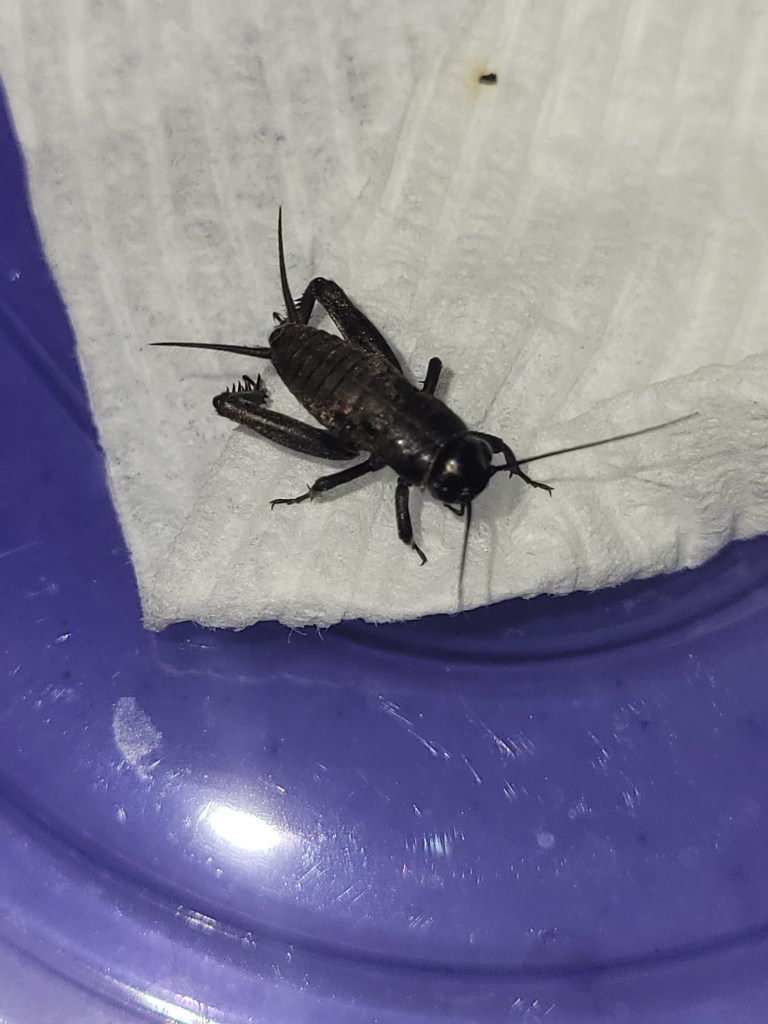

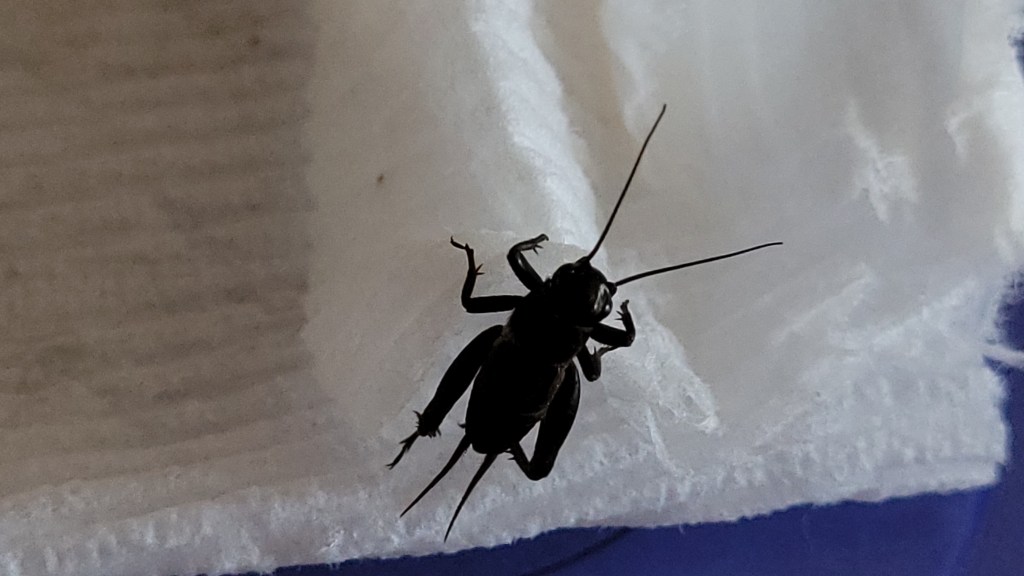

Late last summer, my children found a little black cricket in the basement, which they lovingly named “Crickey.” Crickey was lucky to have been found by the children instead of our cat, who is in the habit of eating only the legs off insects before swatting them around for a few minutes then losing all interest and sauntering off. Crickey was an overnight celebrity in the Hicks household. In the blink of an eye, the children and my wife made her (female crickets are easily identified by the long “stick thing” protruding from their rear end, which is called an ovipositor) an enclosure fully equipped with sticks, grass, carrots, apple slices, a cut in half cardboard tube, and damp paper towels for water. The kids watched Crickey with intoxicating excitement and wonder. We would get real-time updates about what Crickey was eating and what Crickey was doing. The pleasantly haunting sounds of over-the-top children’s laughter echoed throughout the house for the week or so that we had Crickey before returning her to the great outdoors.

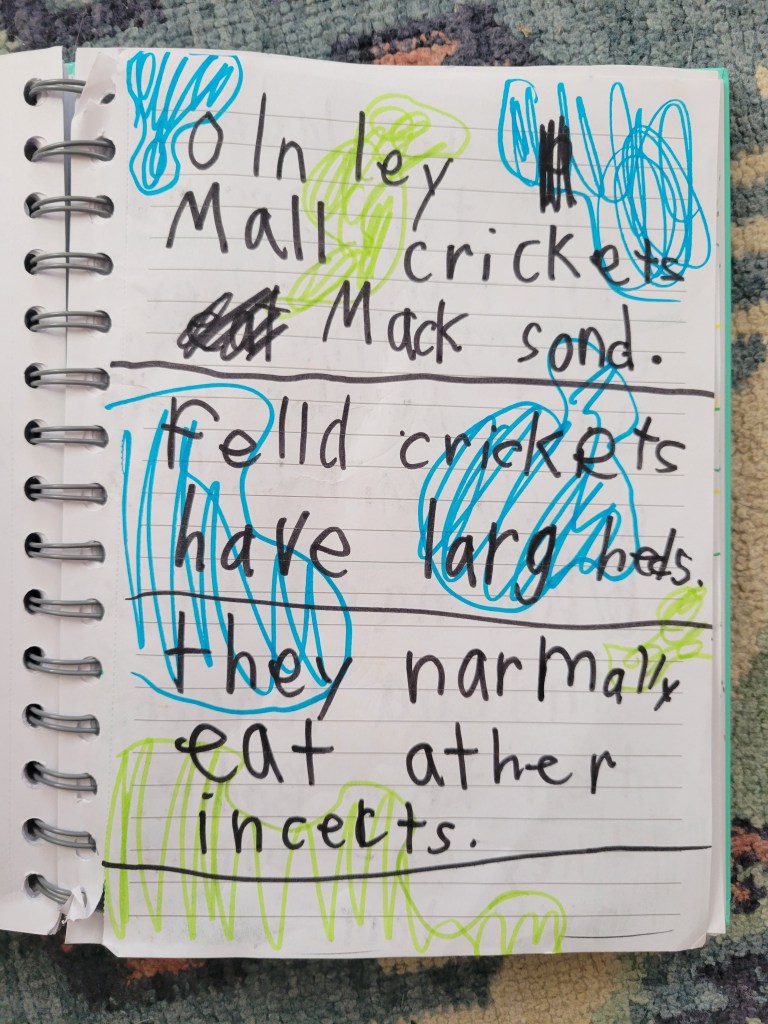

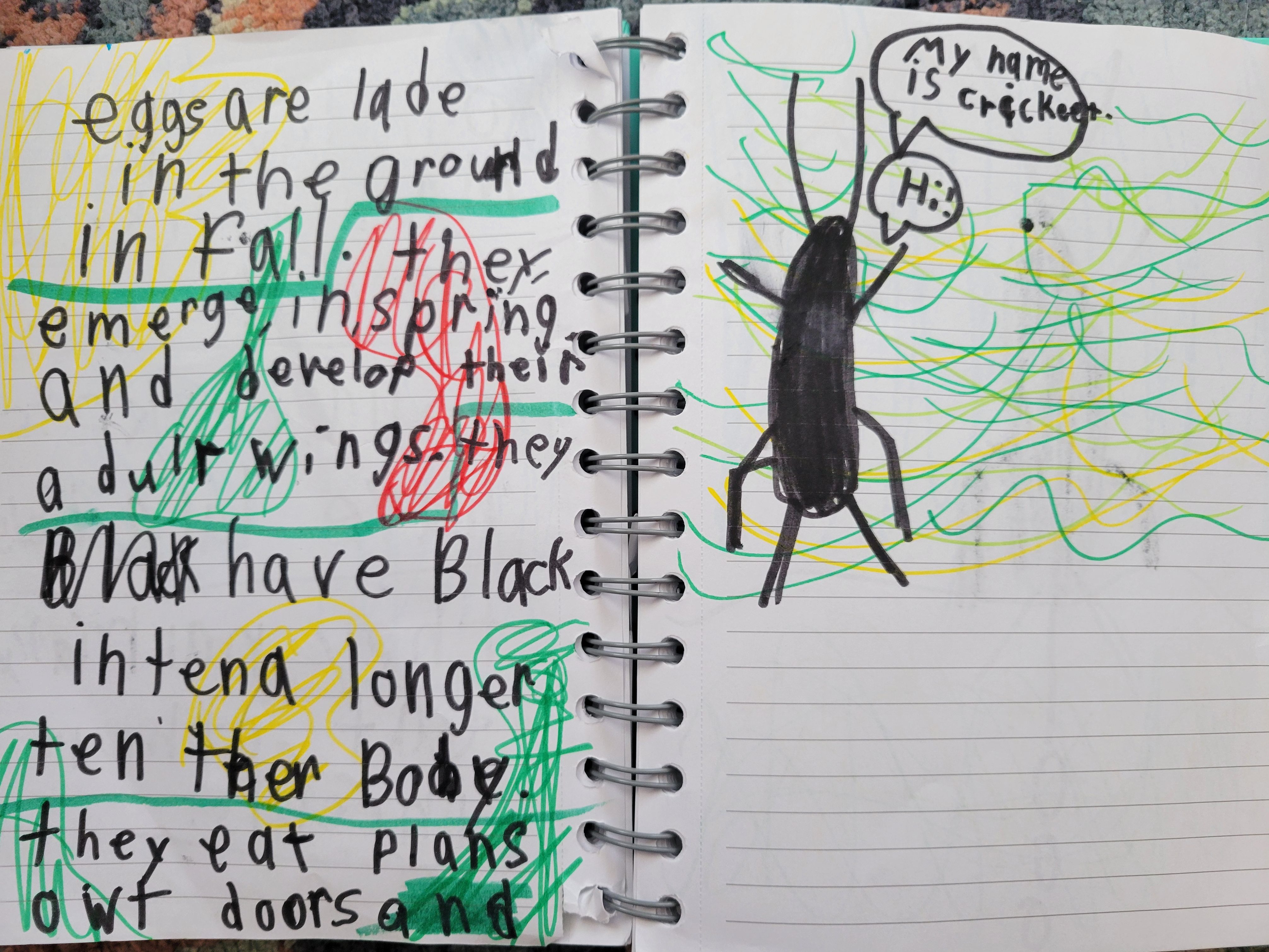

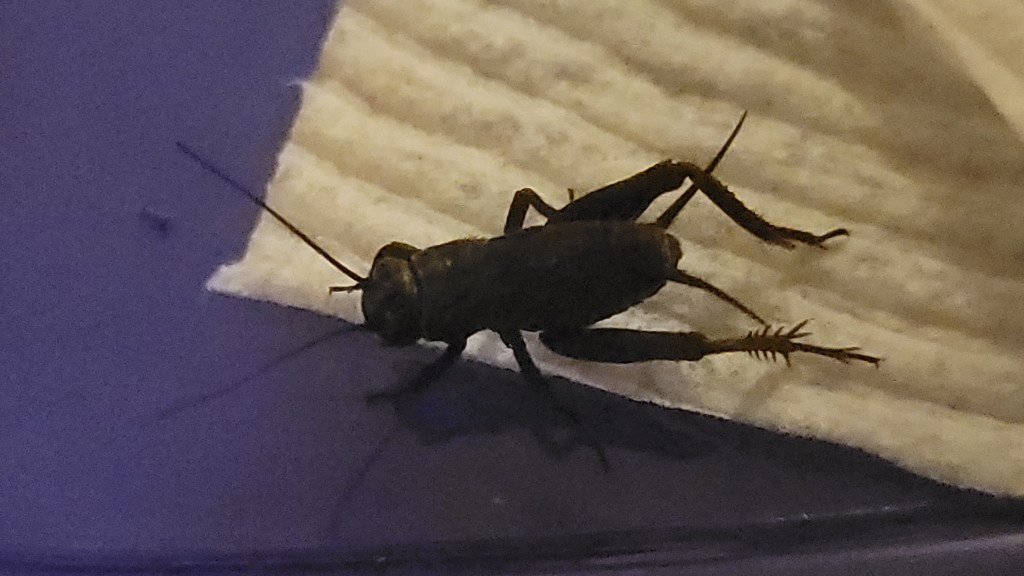

I hadn’t thought about it until it happened organically, but crickets make great temporary pets for kids as they are very easy to care for, won’t bite, and are generally “good” natured. Crickets are omnivores, which means there isn’t much they won’t consume. In their natural environment, field crickets will eat seeds, vegetation, fruits, vegetables, and dead or dying insects. The term “Field Cricket” is the common name for the subfamily of crickets scientifically called Gryllinae. “Field cricket” is therefore a broad term for a number of different species, but they are characteristically very similar: brown to black in coloration, large heads, medium to large-sized crickets, long antennae, strong hind legs perfected for jumping, and are known for serenading the night air with their chirping songs during summer and fall.

Because so many field crickets share similar habitats and look enough alike, their songs are often used to identify and differentiate the species, as each has unique chirping patterns. While on the topic of cricket chirping, let’s take a moment to discuss how they make these sounds. Although their song is often depicted as being produced by rubbing their legs together in cartoons, this is not exactly accurate. Grasshoppers rub their hind legs against their forewings, which is how they produce their songs. Crickets, on the other hand, rub their specialized forewings together to produce their songs. One forewing has a file-like edge, and the other has a scraper edge; think of it like using your fingernail and running it against the teeth of a comb. That is essentially how those chirping sounds are produced, but just at a much, much higher frequency and at a speed our fingers can’t match. This method of song-making is known as stridulation.

Chirping is performed by male crickets to attract females for mating, but there isn’t much of a difference between the songs of the males within the same species, and the tempo of the song fluctuates with the temperature. The hotter the weather, the higher the frequency of the chirps. It is hypothesized by entomologists that female crickets choose males based on proximity; whoever is closest seems to be the mate she chooses. This is contested by some studies though, which show that when population numbers are low, females will opt for males that chirp with more intensity.

Female crickets will lay their eggs in the soil using what is known as an ovipositor, which is a specialized structure that allows insects to lay eggs in specific places. These may be interpreted as a stinger by some, but I assure you they are not. Female field crickets will lay up to 50 eggs at a time; females can produce up to 400 eggs within their lifetime. The eggs hatch in about 2 weeks, unless they are laid in late summer or fall, in which case they will overwinter and hatch in spring. The adults will attempt to overwinter in debris, underground, and sometimes they will seek shelter in our warm and cozy homes. This was exactly what happened with my children’s second pet cricket, which they named “Crickeet” (pronounced crick-eat).

It was late November when Crickeet was found wandering about on the kitchen floor. The kids immediately claimed that Crickeet is the son of Crickey; rather than argue the improbability of this, I was just happy they were able to recognize male from female crickets. With it being winter, Crickeet stayed with us until late February. He lived like a king in his makeshift home. My wife and kids would give him fresh water towels daily and made sure he had plenty of fresh produce; he even grew fond of my wife’s famous banana waffles. There was one incident where his container was left slightly open, and he managed to make his way across the house and under the couch. A wanted poster was drawn up and we had the local news on the line ready to run the story, but he was found before the report hit the air waves. Crickeet was a young, immature cricket, and I was able to identify him as Gryllus pennsylvanicus; his common name is Fall Field Cricket.

As the name implies, they tend to be more active in late summer and fall. Although Crickeet was an immature male and thus not able to sing, I was able to narrow down his species by a few physical traits specific to his species. The fall field cricket has antenna that are usually longer than the lenght of the body and they have cerci (two appendages that extend from the abdomen and are used for sensing vibrations) which are longer than the head and protothorax. Crickeet started to have problems with his back legs, which is evidently caused by a virus known as Cricket Paralysis Virus (CrPV). This virus will unfortunately lead to the death of the cricket, so we decided to let him go when we had a streak of warm weather so he could enjoy what was left of his life outdoors.

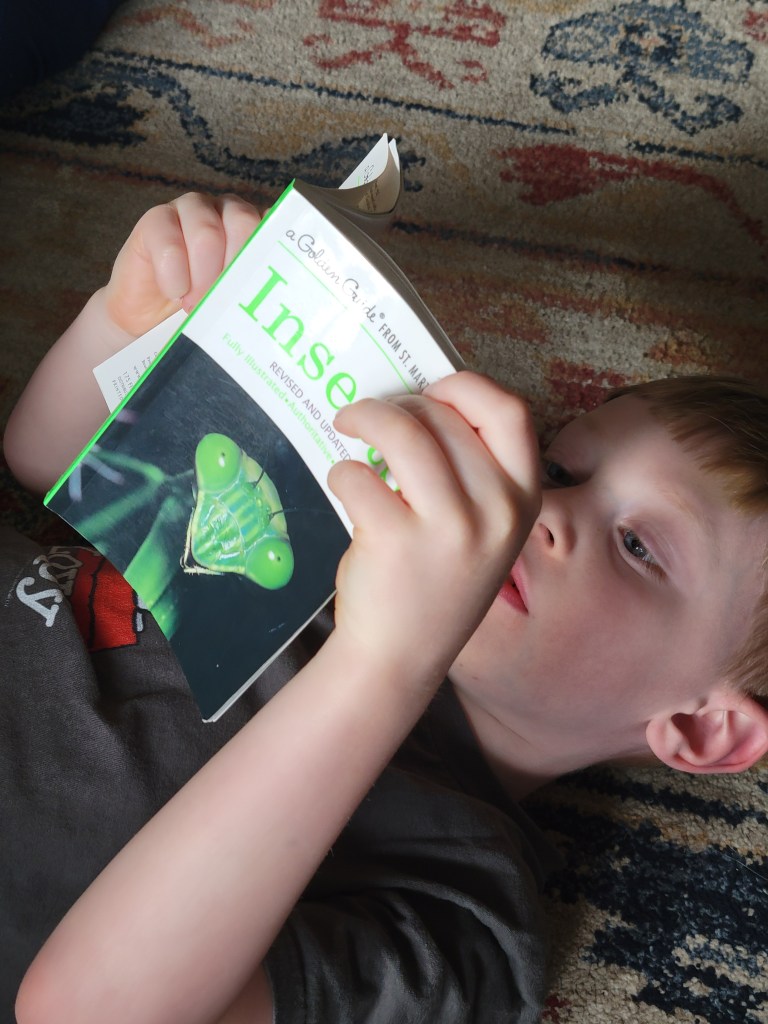

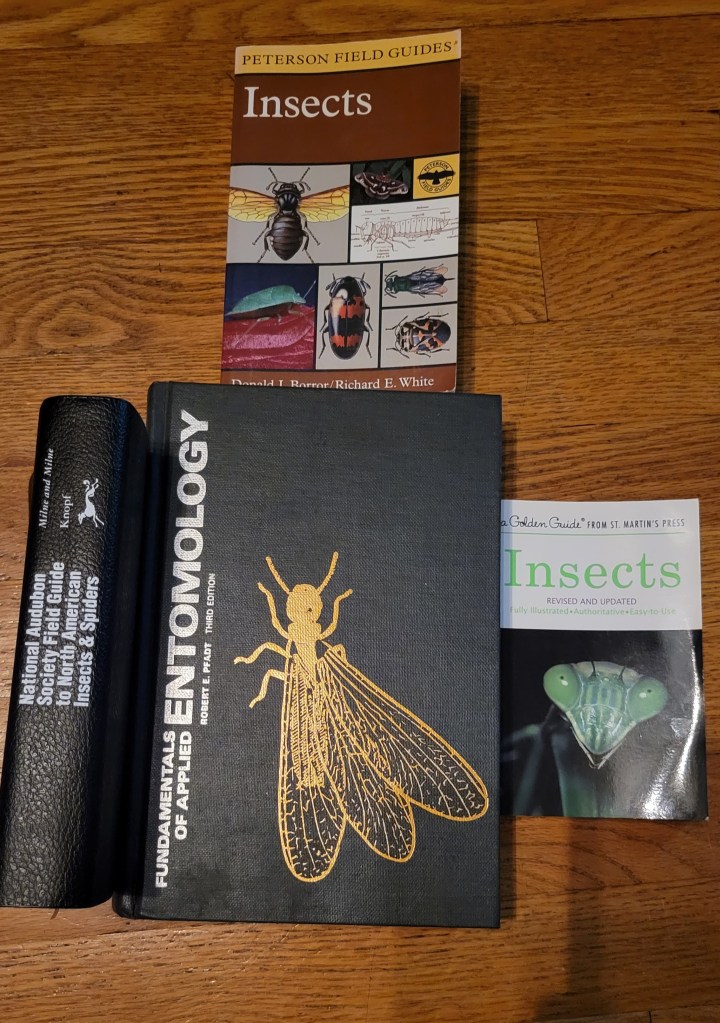

The kids really wanted to get involved with my website and demanded that I do an article about Crickey and Crickeet, which I agreed to as long as they did the research. I provided them with some insect books and helped my daughter with spelling for research on our tablet and through YouTube Kids. My son, Archie, who is not yet an avid reader, assisted by watching videos and finding pictures of crickets in books, which Mary would then read. I am so happy that they are interested in the natural world and that they respect and enjoy the life around them. Although Crickeet may not have been able to ensure his gene pool lived on, his memory will always have a spot in the hearts of the Hickses. I hope he is hoppy knowing that he sparked so much excitement and curiosity in my little backyard biologists.

References:

Milne, Lorus and Margery. (1980), The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Zim, H.S. and Cottam, C. (2001), Insects, St. Martin’s Press, New York

Borror, D. J. and White, R. E., (1970), Peterson Field Guides: Insects, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York

Pfadt, R. E., ( 1978), Fundamentals of Applied Entomology (3rd edition), Macmillan Publishing Co., INC., New York

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/field-crickets

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gryllus_pennsylvanicus

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gryllinae

Crickets

Leave a reply to Tyler Hicks Cancel reply