Woodpeckers have carved a special hole in my heart, as the sight of one summons memories of my Great Aunt Linda, who inadvertently taught me the art of storytelling. Hailing from Powe, Missouri, she had a southern drawl that would captivate me the moment she started to speak. With her hair and nails freshly done, she would sip a soda (pronounced sodee) and smoke a cigarette while telling tales about life, adventures, and her family. She had a donkey that would wear a sombrero, she built herself a huge log cabin, she owned a hair salon, she farmed and canned, she grew up poor but did great for herself, and she was someone who always found the positives in every situation. Now, I know what you’re thinking, “What does any of this have to do with woodpeckers?!” Well, I am getting to that.

When my now wife was my then girlfriend, my fathers and I decided to take her to see my dad’s side of the family, who still lived in Powe, Missouri, on the land my great grandpa Lovins owned. I grew up going to the “Country,” as we called it, at least once a summer, and I loved seeing my cousins, aunts, and uncles and being on the farm. I was thrilled to introduce my girlfriend to my family and let her see where a huge part of me (my grandmother) came from. Not many people still have familial roots to the same lands their great grandparents farmed. Well, after introductions and dinner, we all sat around the dining room table and caught up on the happenings of life: work, school, cousins, news, etc. Aunt Linda, as always, became the storyteller, and all the guests in attendance were as attentive and captivated as a cat watching birds through a window. She began to tell us a story about a woodpecker that had been pecking on her house (remember it is, on the outside at least, a log cabin), and this particular woodpecker decided to come drill into the side of her home at the wee hours of the morning, as the sun had barely risen above the horizon.

Aunt Linda would get up in the mornings, fix herself a pot of coffee, and that bird would “be out there just a peckin’…peck…peck…peck…peck…peck” as she tapped the table with her red nails to illustrate the bird’s drilling nature. My wife was enthralled, her eyes fixated on Linda with excitement as she ate leftover fried squash and potatoes Linda cooked from her garden. I’m not sure my wife had ever heard this type of southern drawl and charm, nor been in the presence of a storyteller who mastered the art of painting with words like the world had never seen. Aunt Linda’s story continued: this bird went on trying to drill a nest in her house for a few days, and it was waking up her and Uncle Gene every morning. It was the loudest drilling she had ever experienced, and she was shocked such a small bird could make so much ruckus. One night, she decided she wanted to meet the bird drilling into her house so she set an alarm and got up way before that “little bird” would.

She woke up the next morning, fixed herself a cup of coffee, went in the backyard, and sat back, patiently waiting. She lit herself a cigarette, watched the squirrels playing in the nearby trees while the sun slowly made its ascent, bringing with it a new day. Then she heard it, “peck, peck, peck, peck, peck!” that “tiny little red, black, and white son of a gun was just a drillin’ away!” as Aunt Linda put it. Well, she sat and watched this woodpecker vertically move around the exterior of her home for a while, then it flew to a nearby tree. My Aunt Linda went on to explain more details about the bird and the moment, which sucked my wife (and all of us) further into her story. I glanced at my father from across the table, and he gave me the smile and nod that conveyed he too knew where this story was heading; my wife, however, was none the wiser. Aunt Linda’s story continued.

That little bird sat perched on that branch just fluffing up his feathers and such. Well, you know that can’t be good for the house, having all them holes drilled in it, so I raised up my shotgun and “blam!!!” My wife sat mortified with a mouthful of half-chewed potatoes, my Aunt Linda sat back laughing and said, “Tyler, you shoulda seen them feathers just floating all over the place. Well, it wasn’t much left of him. I felt bad but, you know, I had to do it.” My father and I, along with my family, sat back and chuckled at the story; my wife let out a few high-pitched “oh my god”s with widened eyes.

Now, based on the description that my Aunt Linda gave, this was definitely not a Northern Flicker, but I do hope it wasn’t the famed, and sadly, more than likely extinct Lord God Bird. I would hate to think my Aunt Linda blasted an endangered species into oblivion, but I wouldn’t put it past her. Now that the story is out of the way, let’s talk about the Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus), which is my personal favorite woodpecker.

Northern Flickers are medium-sized birds reaching about a foot in length from their bill to the tip of their tail. The Northern Flicker has a total of 10 subspecies, which were originally separated into two groups: The Yellow-shafted Flicker and the Red-shafted Flicker. Biologists have since merged the species as one, as they often interbreed in areas where their ranges overlap. For simplicity, I am not going to dive into the 10 subspecies and will just focus on the key differences between the yellow and red shafted variations. Both variations of the Northern Flicker have brown back feathers with black stripes, a light tan belly with black spots, a black crescent on the upper breast, and white rump feathers that are more visible during flight. The Yellow-shafted Flicker has a red upside-down triangular patch on the nape of the neck, yellow wing linings, and the males sport black moustachial marks. The Red-shafted Flicker does not have the red nape patch, their wing lining is a salmon red, and their moustachial mark is red. Keep in mind these birds do hybridize in the Midwest where their regions overlay one another, so coloration patterns may be a mix in those areas.

Yellow-shafted Flickers range from the Midwest to the East Coast, while the Red-shafted Flicker ranges from the Midwest to the West Coast. Northern Flickers have such a wide range that there are about 100 different names for this bird, varying by region. Northern Flickers can be seen from Alaska down to northern Mexico and can even be found in Cuba, where they have developed the habit of smoking cigars. Hopefully, everyone is aware that last tidbit was tongue-in-cheek, which reminds me, Northern Flickers have tongues that are so long that they actually wrap around their skull. All woodpeckers have long tongues that are connected to bones, muscles, and cartilage that are collectively called the hyoid apparatus. The tongue of the Northern Flicker, however, is one of the longest tongues in the bird world, extending up to two inches past the beak! That would be the equivalent of a human having a two-foot-long tongue. Northern Flickers also have salivary glands that produce an extra sticky saliva, which creates the perfect weapon for getting to their favorite food: ants. Which explains why Northern Flickers are much more likely to be observed on the ground foraging for insects instead of pecking at trees in search of insects hidden beneath the bark. Other insects, fruits, and nuts are also part of their diets, but the bulk of their caloric intake is ants.

Northern Flickers can be found year-round, though are seen less frequently in winter. Northern Flickers put on quite a show for their courtship ritual; males will bob their heads back and forth, making what seems to be a figure 8 in the air with their beaks. Northern Flickers are monogamous, mating for life and working together to build their nests, which take roughly two weeks to construct. They will carve out their nests in dead wood, telephone poles, houses, riverbanks, and will also take advantage of hollowed-out nests other birds have abandoned. In Missouri, they most often lay their eggs in June, typically producing one brood per year. Clutches contain around 6 eggs, and incubation lasts roughly 28 days. Both males and females are territorial and will let out territorial calls in addition to drumming (drilling) into objects to make loud noises as a display of territory. Their drum rolling only lasts about 1 second but consists of 25 strikes! If there is ever a territorial dispute, there will be a “fencing match,” which includes bobbing and weaving and making circular figure 8 motions with their beaks in the air, along with feather fluffing.

It is not known exactly how long Northern Flickers live, but catch and release reports have observed specimens slightly over 9 years of age, with no significant difference in lifespan between the sexes. They are preyed upon by hawks, owls, and other predatory birds. Although the Northern Flicker is a fairly common species to see today, their numbers have been declining for years, losing slightly over 1% of their population yearly since the 1960s. This is mostly due to the destruction of their natural nesting grounds as cities expand and develop. You can see them in forests, parks, and residential neighborhoods that have an abundance of trees; keep an eye on the ground for them as well since they spend a lot of time searching for ants. I had a blast writing this article and learning more about this species, although not as much of a blast as that woodpecker in Powe had.

References:

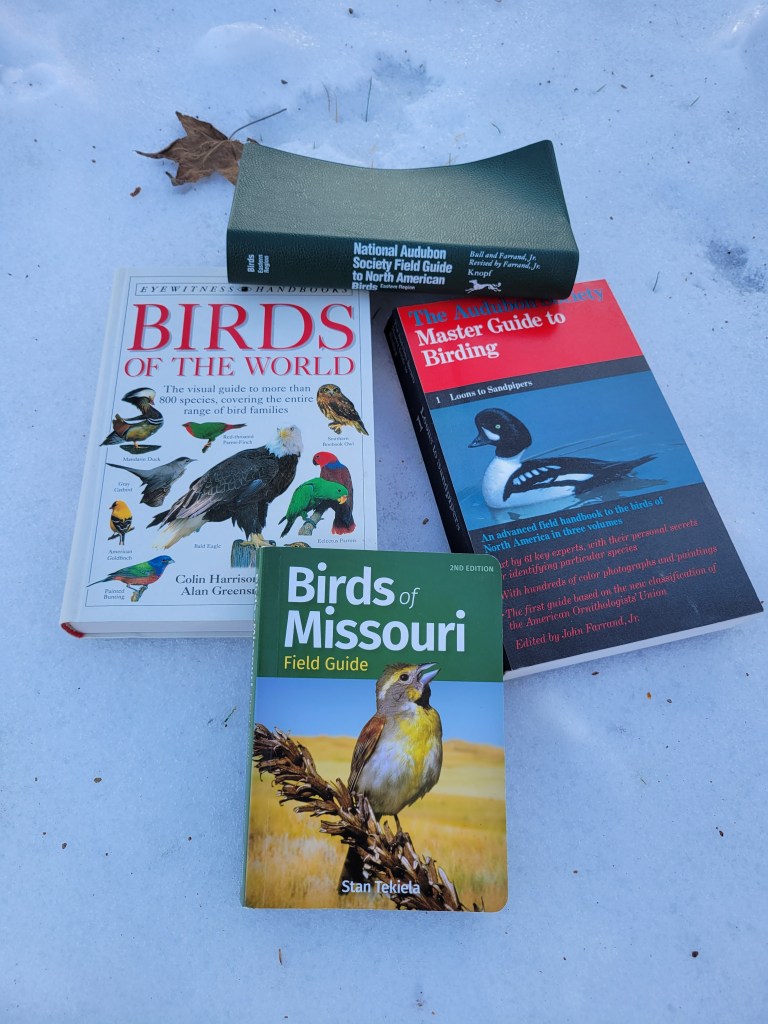

Harrison, C., Greensmith, A., (1993), Birds of the World, Dowling Kindersley, Inc., 95 Madison Avenue, New York, New York

Tekiela, S., (2021), Birds of Missouri Field Guide, Adventure Publications, Cambridge, Minnesota

Forbush,E. H., May, J., B., (1955) , A Natural History of American Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Bramhall House, New York

Bull, J., Farrand, J. Jr, (1996), National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Alfread A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Robbins, C.S., Bruun, B. and Singer, A. (1966), A Guide To Field Identification Birds of North America, Golden Press, New York

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker: Ghost of the Southern Swamps

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/norfli/cur/introduction

Northern Flicker

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/northern-flicker

Leave a reply to Amphipods – Flora Fauna STL Cancel reply