Sometimes in life the little things are what matter most, or at least that’s what I have been told. Being in the doghouse, I decided taking out the trash would be a strategic way to earn some small but compounding good points with the wife. I’m not confident that act alone put the doghouse in the rearview mirror, but I am sure it had some measurable impact. Jokes on her though, I don’t mind taking out the trash because it gets me outside and you never know what critters lurk beyond the threshold. On this particular day I spotted what looked to be a ladybug on steroids. Its color differed and its body structure differed slightly as well since it had less of a neck than a ladybug does.

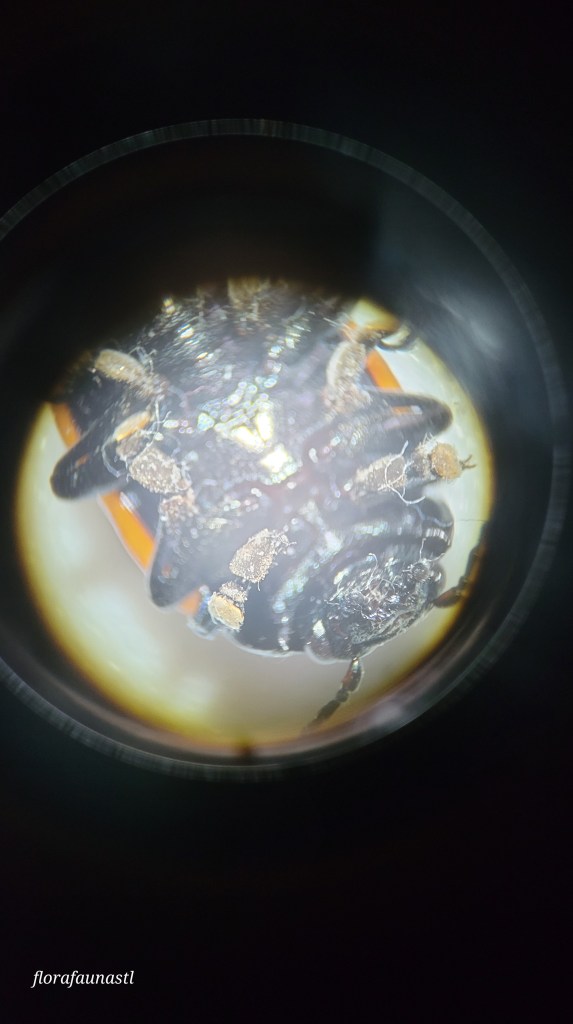

I keep my trusty old local honey jars in the garage for occasions like this and made a dash for the garage. Upon my return, this beetle must have known what was coming and decided that dropping to the ground among the foliage was the best course of action. This dropping off tactic is common among many beetle species. Biscuit (my dog), ever the observant sidekick, plunged into the foliage to retrieve/eat the beetle. Thankfully, I was able to locate the beetle and get him in the jar before he became a small dose of protein. I got him under the microscope, took some videos and pictures, and went into research mode. I found the match in my handy insect book; this was a Labidomera clivicollis, common name: Swamp Milkweed Leaf Beetle.

Appearance-wise, these guys look like massive ladybugs, but they are actually in separate families. As the name implies, the swamp milkweed leaf beetle is commonly found along streams and in marshes but can also be found anywhere that milkweed grows and ranges throughout most of North America. With the exception of a uniform black Rorschach-inspired “X” pattern on their elytra, each individual possesses unique markings. Elytra are the hardened forewings that are unique to the order Coleoptera (beetles). The elytra protect the hindwings, which are used for flying. The order Coleoptera makes up just shy of 40% of all known insect species and accounts for roughly a quarter of all known animal species. Swamp milkweed leaf beetles have dark blue or green heads and legs; their elytra range from orange to yellow in color. This color palette is common among many of the insects that feed upon Asclepias, a genus of plants that we refer to as milkweeds.

The majority of milkweed is toxic to most animals because they produce a toxic milky fluid that contains cardenolides (cardiac glycoside), which, if ingested, can be fatal. As the toxin name suggests, it can cause heart rhythm issues, cardiac arrest, breathing issues, and death if large doses have been ingested. Even small doses can cause confusion, nausea, stomach issues, and seizures…so it’s probably best to avoid ingesting any milkweed. Unless, of course, you happen to be one of the insects that has evolved to safely ingest milkweed toxins (none of you reading this fall in that category!). The swamp milkweed leaf beetle has evolved to eat this plant, along with monarch butterflies, milkweed bugs, oleander aphids, and red milkweed beetles, to name a few. Some of these insects store the toxins from the plant in their bodies for defense.

Consumption of these insects will result in extreme foul taste and potentially gastrointestinal issues. All of the species of insects listed above share a common theme: colors of red, orange, yellow, and black. This is known as Müllerian mimicry, which is when two species that have honest warning signs (meaning they really are toxic) come to share the same color patterns as a warning to predators. This is mutually beneficial to all of these species because it teaches predators quickly that this particular color pattern equals foul taste and stomach pains. So if a bird eats a milkweed bug, it’s probably not going to risk it and sample the swamp milkweed leaf beetle afterwards simply due to the similar coloration. This is also a perfect example of aposematism, which is when a species presents colors that warn predators of its toxicity.

The swamp milkweed leaf beetle will feed specifically on the leaves of milkweed plants and has been observed biting off the edges of the leaf’s veins in order to let some of the milky toxin drain before eating the leaf. They mate and lay eggs on their host plant; the female cements the eggs to the underside of the leaf. In about a week, the eggs will hatch and the larvae will go about eating the plant as well as other larvae and eggs of other insects and even their own species. The adults do not guard the eggs and have also been observed cannibalizing the eggs of their own species, but not their own clutch. After a few weeks, the larvae will drop to the soil and pupate, emerging a few weeks later as adults. There is not much known about the lifespan of this species, but adults do seek shelter in mullein leaves once autumn approaches in order to shield themselves from winter. So at the very least, it is safe to assume they live at least a year. For the record, these beetles are harmless to humans and don’t seem to mind being handled.

The research I did on the swamp milkweed leaf beetle has really opened my eyes to how specifically unique plant and animal relationships can be. I have captured video and pictures of a few other milkweed denizens and will be writing articles for them after some more research has been done. Until then, enjoy the wonderful autumn air and go explore!

References:

Milne, Lorus and Margery. (1980), The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Zim, H.S. and Cottam, C. (2001), Insects, St. Martin’s Press, New York

Borror, D. J. and White, R. E., (1970), Peterson Field Guides: Insects, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York

Pfadt, R. E., ( 1978), Fundamentals of Applied Entomology (3rd edition), Macmillan Publishing Co., INC., New York

https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/asclepias_syriaca.shtml

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/swamp-milkweed-leaf-beetle

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milkweed_leaf_beetle

Leave a reply to Terri Cancel reply