I have two very fond memories of blue jays, both are as dramatic a contrast as the view of this particular bird itself. First, I have a strong detailed memory of my Grandma Joyce throwing bird seed out into the snow-covered yard. She would have her cigarette, I would have my Little Debbie oatmeal sandwich cookie, and we would look out into the cold waiting for birds. We would get so excited when we would see cardinals and our shared favorite and star of this post, the blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), land and bring color to an otherwise white and gray wintry world. The blue jays would gather round, typically in pairs, and peck their winter alms from the snow. Occasionally, they would share the feast with sparrows, but their calls usually frightened them back to the bushes where they lived.

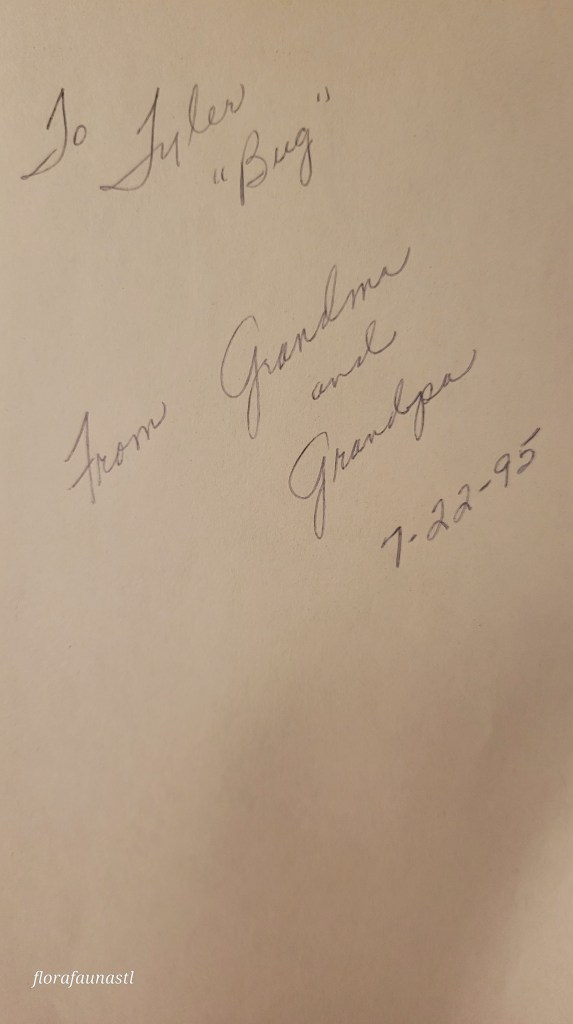

Grandma Joyce was, no, IS one of the foundational pillars of my love for nature, and this memory is one of those pivotal moments in my love for the world. The opening of one’s awareness to the life around you, and the appreciation for it. She would feed this passion of mine with subscriptions to Zoo magazine, books about animals (one of which I actually used for this post), and countless hours of nature documentaries, not to mention the trips to parks where I would roam free in the woods and discover the natural world.

All of this said, to me, the blue jay had solidified itself in my mind as this tranquil winter bird, with the cool blue plumage to match. Their signature blue color is not due to blue pigmentation in the feathers themselves, but rather is a result of light reflection or interference with the internal structure of the shaft. Which means that if you find a blue jay feather and break or crush the shaft, the feathers will lose their coloration. A quick run-down on feather anatomy here. The shaft is the stiff stalk part of the feather, the bottom part that sticks into the bird’s skin is the quill, the rest of the shaft is referred to as the rachis, and this is where the barbs are connected. The barbs are the colorful structures that you see when you think of feathers.

Now to be specific, there are a few different subspecies of blue jays in North America, but the ones pictured here, and the ones I see most often, are called Coastal Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata cristata) and they range from North Carolina to Texas and are a vibrant blue. They are fairly large birds, reaching lengths of up to 11 inches. Originally, their ecosystem of choice was broad woodlands, but they are highly adaptable and can now be found throughout city neighborhoods, parks, farmlands, and really anywhere with trees. In St. Louis, they can be found year-round, although some individuals do migrate in and out of our state. Their patterns of migration remain a mystery, individuals have been observed migrating one year and remaining the next, with no definitive pattern it is presumed to be tied to certain weather conditions. In the event of migration, the birds can sometimes be seen forming loose flocks, but they are otherwise solitary, with the exceptions being mobbing and love.

Blue Jays are monogamous and the pairs will bond for life, which is actually a huge commitment since they can live for at least 25 years if not more! That’s on the extreme end of the spectrum though as the average lifespan of wild birds tends to be around 7 years, give or take. The mating season ranges from early spring through mid to late summer, typically peaking in late April. The males will engage in aerial pursuit of females, sometimes offering her food. Once they have found a match, they will begin to build their cup-shaped nest using twigs, roots, paper, feathers, plant matter, bark, moss, and any other materials they deem fitting. They will construct the nest in any type of tree but prefer to build in the cover of coniferous trees, think Christmas trees. This choice of home further solidifies my association of these majestic birds with winter. They may sometimes utilize the nests of other songbirds, such as robins. They will lay an average of 4 to 5 greenish-blue eggs with brownish-gray spots. Being team players, both parents will incubate the eggs over the course of 16-18 days. The young will fledge (become capable of flight but not full-on flying) about 20 days after hatching. Once fledging is complete and the young can fly, they will travel with their parents until fall when they must set out on their own.

Blue Jays are known for their loud and over-the-top calls and are often referred to as the alarm of the forests. They are quick to inform the animals around them of predators. They will even go so far as to dive-bomb hawks and owls at the mere sight of them. Often mobbing the predatory raptors until they leave the area. They have a wide range of vocalizations and will mimic other songbirds and sometimes even mimic hawks to scare away birds from bird feeders. Speaking of bird feeders, let’s circle back to the beginning of this post, my Grandma Joyce throwing out wild bird seed in the winter for her favorite birds. They love acorns, wild berries, and my grandmother’s wild bird seed mix, and they eat the occasional insect, but what bird doesn’t? They also hide thousands of nuts throughout the year, much like squirrels, and pull from their caches when food is scarce. It is said they contribute significantly to the rebuilding of forests with all the forgotten planted seeds. In fact, there is an old African American folktale that attributes the blue jay to the creation of earth. The blue jay brought the dirt and planted the seeds when the world was nothing but water, and thus formed the land and the forests.

There is, however, a contrasting folktale about the blue jay, in which the bird is employed by the devil himself. The job was simple, each Friday the blue jay was to bring sticks to hell in order to feed the fires. There are a few variations as to why the bird must visit hell once a week, but some of their habits definitely led to their association with Satan.

This is where my grandma Joyce’s understanding of blue jays ends and my wife’s begins. It was mid-summer of 2020, and we had some new neighbors move in. The kind of neighbors that are loud and obnoxious. On top of that, you see them doing questionable things such as attacking animals at random, dive-bombing playing children, stealing nests from other birds via eating the eggs, eating carrion, and decapitating other birds. Now, to be fair, blue jays rarely eat other birds, but they have been observed to do so… and they like them young and helpless, preferring fledglings.

Did I witness the blue jays killing young birds? No, I did not. However, the nest they were residing in, which was inconveniently right next to my back door, was an inhabited robin’s nest… until the blue jays showed up. Now, I did not witness firsthand the gobbling of the robin’s eggs, but I can say mother robin was in the nest one day, and then she was replaced a few days later.

My second fondest memory of blue jays is one involving my wife, my 6-month-old son, and a pair of angry blue jays. We had been dodging blue jay attacks every time we took out the trash or had to get in, or out, of the car. On this particular day, we were on a walk with our son, and we were just about home. We heard the angry calls and picked up our pace as we headed for the house, my wife pushing the stroller. By this point, my son was starting to cry, my wife was getting nervous, then… the attack happened. They started dive-bombing her, pecking at her head, and pulling her hair. She screamed and gave my son’s stroller a hard push and ran away with her arms flailing about like a muppet, screaming and being pursued by these overly protective birds. I grabbed the abandoned stroller rolling down the sidewalk, ran for the garage, and started frantically entering the garage door code. The garage door slowly opened while my wife reenacted the 1963 classic “The Birds,” doing her best Tippi Hedren impersonation. The blue jays played their part exceptionally well. My wife eventually made it safely into the garage, both eyes intact, and just a few pecks to the head. Needles to say, the hawks were kept away that summer, mobbed by this pair of jays and their kin.

This highly territorial behavior has led to some people seeing blue jays as pests, much like their corvid cousins, the American crow. Innocent bystanders are mobbed by them, fleeing for their lives. Bird watchers look on in fear as they watch the blue jays scare away the other birds from the bird feeders or steal nests. Hunters, human and animal alike, lose their prey as a result of the blue jay’s raucous alarm, going another day without food.

The behaviors of the blue jay have positive outcomes for some and negative outcomes for others. My memories of Grandma feeding them in the winter and appreciating their beauty contrast sharply with the memory of my wife’s battle with our aggressive summer neighbors. I have grown to see, the blue jay represents the duality of nature, the Ying to the Yang, the summer to the winter.

References:

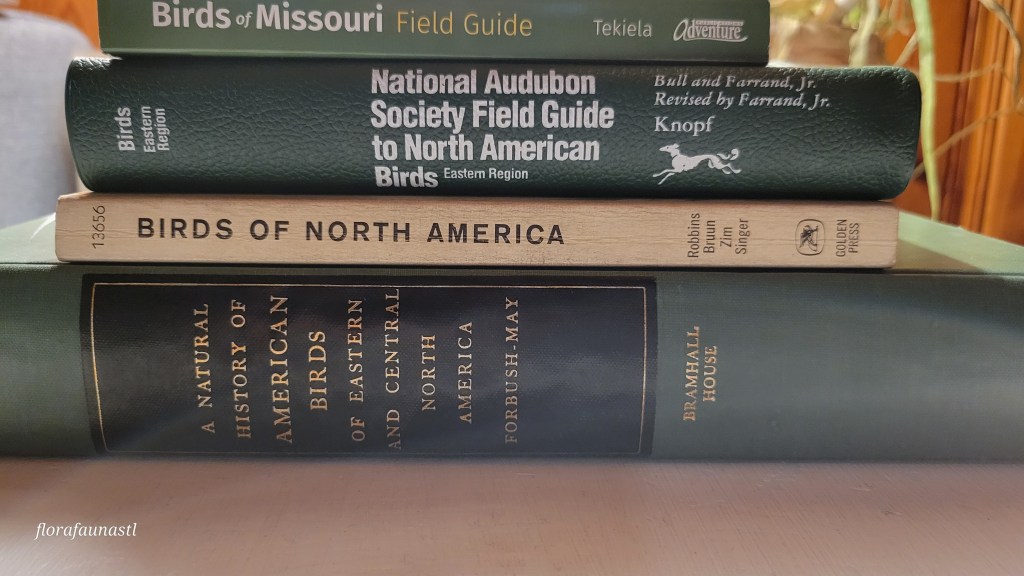

Robbins, C.S., Bruun, B. and Singer, A. (1966), A Guide To Field Identification Birds of North America, Golden Press, New York

Bull, J., Farrand, J. Jr, (1996), National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Alfread A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Forbush,E. H., May, J., B., (1955) , A Natural History of American Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Bramhall House, New York

Tekiela, S., (2021), Birds of Missouri Field Guide, Adventure Publications, Cambridge, Minnesota

Harrison, C., Greensmith, A., (1993), Birds of the World, Dowling Kindersley, Inc., 95 Madison Avenue, New York, New York

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/blue-jay

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_jay

The American South: Blue Jays and Ol’ Prejudices

Leave a comment