I was in search of new species to document for this site and was lucky enough to be biking near the lake at Willmore Park at the right time. As I descended towards the lake, I saw someone fishing who was accompanied by a large white bird. This awkward drifter optimistically stood a few feet from the bench where the fisherman sat casting their line. I am not sure if this is the same American Egret (Casmerodius albus) that is at the park each time I hike or bike the trails, but it is definitely comfortable around people.

I parked my bike and got ready to take some photos when the person fishing announced they had just caught a small bluegill and were going to feed the fairly intimidating and patient moocher. These birds are large, standing a little over three feet tall with impressive wingspans of up to five and a half feet. The larger ones tip the scales at just over three pounds. Mix in their pitch-black legs and feet, serpentine neck, sharp yellow beak, and loud croaks, and you get a bird that’s beautiful and menacing.

The American Egret waited patiently, poised like a dog waiting for table scraps. The fish was tossed in the air and, although it wasn’t caught midair, was gobbled up quickly. They are mainly carnivorous, with diets consisting of fish, frogs, snakes, small mammals, crustaceans, and insects. They usually stand patiently in shallow waters and impale prey that has strayed too close. This particular egret seems to have found it easier to get fish by strong-arming fishermen. I have been told by several fishermen that it will often hang around them waiting for a sympathetic fish to be tossed in its direction.

After eating the fish and taking a few drinks of water, it spread its huge wings and glided to the other side of the lake. Contemplating which fisherman will be the next to pay their dues, I am sure. These birds go by many names: “Great White Egret,” “American Egret,” “Great White Egret,” “Great White Heron” and were almost hunted to extinction in the late 1800s.

During the mating season, they grow long plumes that they fan out for display to attract mates. Plumes are ornamental feathers; regarding egret plumes specifically, they are called “aigrettes,” which is a French word meaning “ornamental tufts of plume.” These attractive and elaborate feathers caught the attention of humans who used them to decorate ladies’ hats. Plume hunters would demolish their nesting rookeries (colonies) to collect aigrettes. This was easy pickings for the plume hunters as American egrets breed in huge rookeries in what are called platform nests.

Platform nests are elaborate and complex nests built utilizing twigs, sticks, and branches. The mother egret lays two to three light blue unmarked eggs in these nests. Often plume hunters would kill the adults and leave the fledglings to starve. The slaughter of these birds was so intense that multiple state Audubon societies fought to conserve and save the egrets. This ultimately led to the creation of the National Audubon Society, hence their logo being an egret in flight. Thanks to their efforts, the American Egret has since made a comeback and has even expanded their territory. They can be found year-round in South America and the southern hemisphere of North America. In the summer months, they can be found throughout most of the Midwest during the breeding season.

The birds will migrate in flocks short distances, going just far enough south to avoid ice. During flight, they tuck their long “S”-shaped necks in (unlike cranes and geese) and are fairly slow fliers.

These beautiful birds have been a backdrop to summers in many of our local parks with waterways or small ponds and shallow lakes. I have spotted them in Francis Park, Tower Grove, and Forest Park. To be honest, I have appreciated them in the same sense I appreciate all of nature but realize now how exceptional and symbolic these birds are. They represent conservation efforts and show that these efforts can be effective. I now see the fish being tossed to the American Egret who stalks the fishermen at the park as a peace offering. Perhaps subconsciously we know we owe them for the brutal ways we treated them. Perhaps they know this as well.

References:

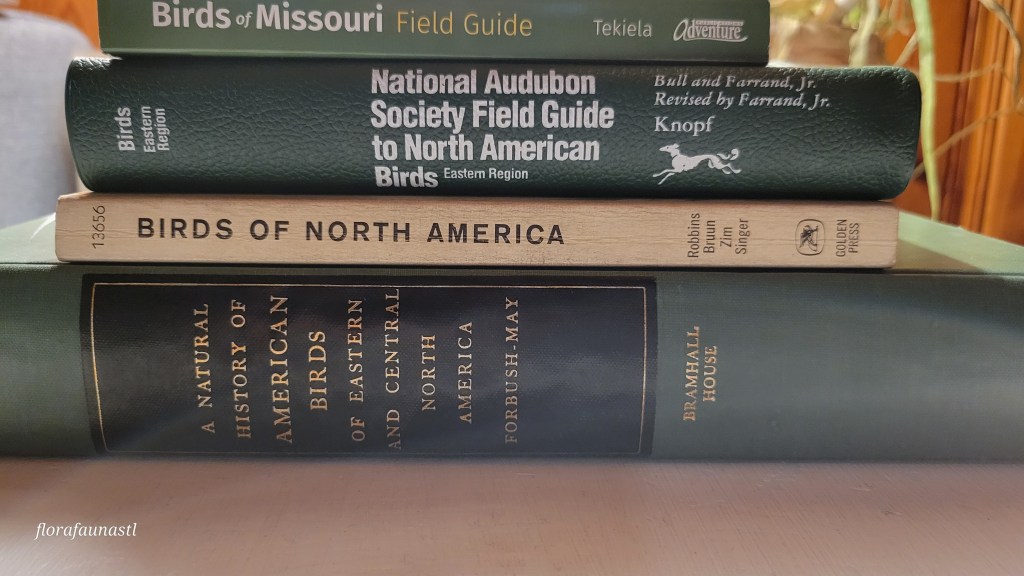

Robbins, C.S., Bruun, B. and Singer, A. (1966), A Guide To Field Identification Birds of North America, Golden Press, New York

Bull, J., Farrand, J. Jr, (1996), National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Alfread A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Forbush,E. H., May, J., B., (1955) , A Natural History of American Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Bramhall House, New York

Tekiela, S., (2021), Birds of Missouri Field Guide, Adventure Publications, Cambridge, Minnesota

Leave a reply to Sharon Linde Cancel reply