Blackburn Park is a go-to for many in the St. Louis region who enjoy a quick break from the city. The park boasts a great playground, beautiful trails, and best of all a wonderful bird sanctuary that hosts more wildlife than just birds. Last week I took my dog Biscuit with me to walk the trails and explore in the hopes of finding the creature my son and I spotted the last time we visited the park. Nestled within the bird sanctuary, there is a freshwater spring that starts just under what I am going to loosely call a small bluff. I love to sit on this bluff and watch the clear water run while I read, talk to my wife, meditate, listen to nature, or watch the kids play around the stream.

It was in this very spot that my son and I first noticed something very small and noticeably white in coloration come to the surface ever so often before jetting back to the stream bed. This is the creature I came back to find with my trusty fuzzy sidekick. Unfortunately, Biscuit was much more concerned with the sounds of the Northern Flickers in the distance and had her mind set on bird watching, so I was alone in my freshwater spring/stream exploration. With Biscuit secured to a tree near the stream, I approached the muddy banks using a long stick to help prop myself up and stop me from sliding into the water. I had a jar in hand and scoured the water with my eyes looking for any sign of life near the location we first spotted the mystery creature. Perhaps it was an isolated population of Tully’s Monster (Tullimonstrum) that had survived unchanged and undiscovered. Jokes aside, I assumed it was some kind of small aquatic insect, like a dragonfly nymph, although it would be early in the season for that. After about 10 minutes of crouching over the edge of the stream, I finally saw the movement I was looking for, a small pale creature swam to the surface, did a small “flip,” then swam back to the stream bed. Slowly, I placed my jar in the water near where it was resting, and the suction of the water into the jar did the work for me. To my surprise, there were two of them in the jar, one fairly larger than the other.

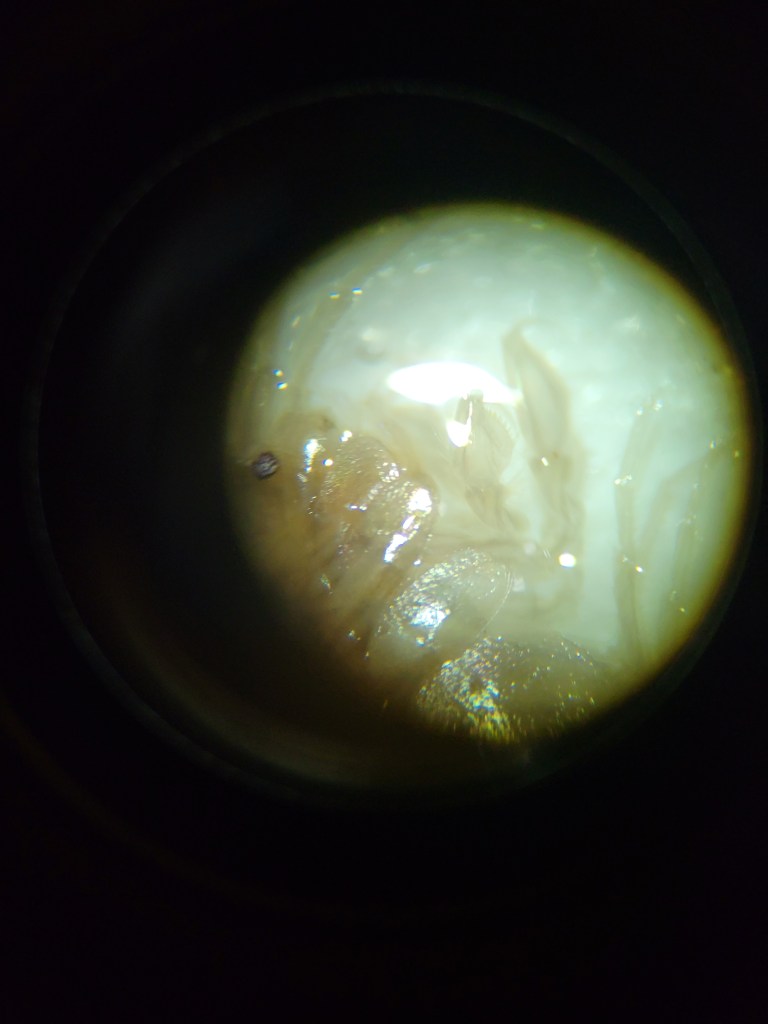

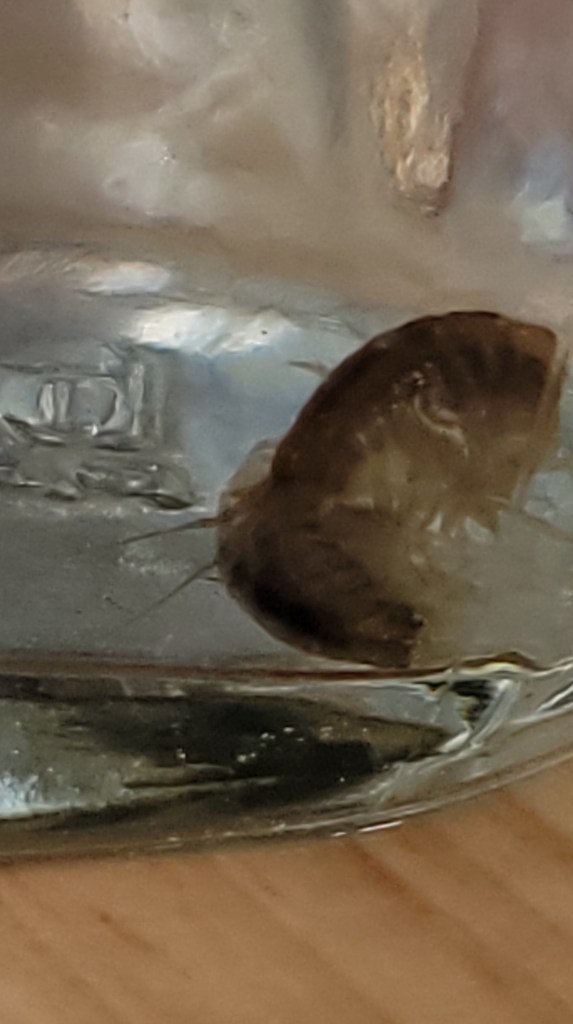

Thanks to the fresh natural spring water being so clean and clear (I am half tempted to drink it), I was able to see the creature clearly. It looked to me like a type of aquatic isopod, or rolly polly/sowbug. With my specimens in hand, I showed the catch to Biscuit, who gave me an approving and uninterested bark. It was the same tone you use when you tell your kids they did something great for the sport of it rather than really being impressed. Time was of the essence here, so I hurried home with my specimens, showed them to my neighbor, took a few pictures and videos with my microscope, and had them back to their stream within an hour. I like to imagine they are still trying to convince their friends that something took them from their home, did experiments, and returned them unscathed only for them to be laughed at and called kooks. While my initial guess as to what these animals were was off, from a biological standpoint I was not very far off. These are not isopods, but rather a different type of closely related crustacean; these are amphipods.

Amphipods are commonly called “Scuds, Sideswimmers, or freshwater shrimp” by fishermen and others who are familiar with them… which isn’t that many. Due to being from St. Louis and my love of Spuds MacKenzie, I decided to name one of these guys Scuds MacKenzie, and he is now the new party animal and will be for as long as I live. Amphipods and isopods have a few things in common; for starters, there are terrestrial and aquatic species of each (Missouri only has aquatic amphipods). They both sport two pairs of antennae, they have eyes that are not on stalks like other crustaceans, and they lack a carapace, which is a hard covering on their back like crawdads have. Now, usually I will try to pinpoint an exact species, but for these guys that won’t be possible. There are almost 10,000 species of amphipods worldwide and of that, almost 2,000 are freshwater species. In the continental United States, there are at least 80 identified species of Gammaridae (the freshwater family of amphipods to which these guys belong), and the only way to really identify accurately involves dissection, which I won’t do. But trust me, that won’t make a huge difference in my high-level introduction to amphipods.

As mentioned already, they are very similar to isopods, but there are some key differences. Amphipods have their bodies flattened laterally, and they have specialized pereopods (their legs); in fact, the name Amphipoda means “different feet.” Amphipod body segments can be grouped into head, thorax, and abdomen, and the pereopods (legs) between the thorax and abdomen are different. The head is connected to the thorax, which has appendages used to help with eating and gripping mates (more on that later), as well as appendages used for locomotion, which are what all the remaining pereopods are for. Amphipod gills, which are used for bringing oxygen into their bodies, are present along the thorax. Although they tend to crawl around on the sediment, the name “Sideswimmer” is accurate as they can actually swim well, but they do so sideways by kicking their tails. Although seemingly shrimp-like in appearance, their tail, which is comprised of three separate uropods, doesn’t actually form into a fan like you would see in true shrimp, though the use of their tails is identical: used for locomotion. Amphipod diets vary, but they mostly feed on decaying plant and animal materials. This dietary habit means they are what biologists call detritivores, which play an important role in ecosystems since they help break down waste. Scuds have been observed to have a darker side, though, if pushed. When food sources are scarce, cannibalism is not off the table. While on the romantic topic of cannibalism, let’s get back to those hook-like claws and talk about how those are used for mating.

Scuds have a mating behavior which is known as amplexus. This means that the males will hold on to the female with those little hook hands (gnathopods) and guard her for anywhere from 2 days to 2 weeks, and the wife says I’m clingy!!! While in this entanglement, the males will use their tails to sweep their sperm into the female’s brood pouch (marsupium); can you feel the romance here? Amplexus only stops once the female molts (sheds her exoskeleton for a new one), and her eggs are then ready to hatch. Females can produce hundreds of eggs per brood, and as they age, they grow, which allows for more eggs to be produced. When the eggs hatch, they look identical to the adults, just tiny versions. Because amphipods are prolific in various ecosystems ranging from caves to streams to oceans and even on land, they are used as bioindicators. This means that by studying amphipods, we can determine if an environment is polluted or if there are changes happening in a given ecosystem.

In Missouri, many of our native amphipods are cave-dwelling amphipods, and due to the disruption of their environments through pollution and human oversight, we have 10 species that are at risk of being extirpated from our lovely state. I hate to always end posts on a note like this, but sometimes you just have to. Blackburn is a beautiful park; most folks come to see the birds and the deer that inhabit the area; I would wager a very small number of us even notice the tiny little amphipods living in the stream of the freshwater spring. A spring that has been there since, from what I have been able to uncover, at least the 1800s, but probably much longer than that. While there last time, I removed a few pieces of trash from the stream and picked up wrappers along the trails. As cool as he was, and as much as we loved him in the early 90s, Captain Planet isn’t coming. There are no magic rings we can use to conjure up an earth spirit in red spandex to save us and our fellow species. BUT, each of us can do things to help keep the world alive: don’t be wasteful, don’t litter, pick up trash if you see it, and don’t think someone else will do it, because they probably won’t. Let’s all be conscious of the world around us a little more so that future St. Louisans can hang out in Blackburn Park, with the real party animal: Scuds MacKenzie.

References:

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/scuds-sideswimmers-amphipods

Scuds or side-swimmers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amphipoda

https://www.webstergrovesmo.gov/171/Blackburn-Park

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captain_Planet_and_the_Planeteers

Leave a comment