Thanksgiving is upon us, and the images and smells of turkey surround us. Our love for the taste of turkey goes back centuries, evident by the fact the Mayans domesticated the wild turkey roughly 2,000 years ago. The Mayans not only domesticated turkeys but also worshipped them, often depicting them in their artwork. “Ulum” was the Mayan word used to describe both wild and domesticated turkey. Turkeys look similar to Guineafowls, which were brought into Europe through trade routes established in Turkey. Because of their similarity, Europeans that arrived in the New World called these birds of the New World turkeys, as that is what they also called the Guineafowl due to their being imported from Turkey. The name stuck, and that is how these birds got their name.

There are two types of turkeys in the world, both hailing from the Americas. The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) ranges from the East Coast to central North America, while the Ocellated Turkey (Meleagris ocellata) is located in Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala. Both species are similar in appearance, although the Ocellated Turkey is a dash more colorful. Turkeys possess what is called a wattle, which is a flap of skin that runs from under the beak to the neck. Males possess what is called a snood, which is a worm-like growth right above the beak. The snood can change in size depending upon the mood of the bird, dropping down low or rising up in the air. Turkeys also have what are called caruncles, which are unique fleshy growths on the head and neck that help to identify individuals. Turkeys have the ability to change the color of all these parts depending on their moods. You read that right; although our imagery often shows turkey heads being red with a dash of blue, they actually change the color of their skin to reflect their moods. Coloration ranges from shades of red, white, and blue. Talk about a true American! They do this by contracting and expanding blood vessels within the skin. Turkeys also have a group of long feathers (up to 12 inches) that protrude from their chest, which is called a beard. Although more commonly found on males, females will sometimes have beards as well, sort of like that one great aunt you only see on Thanksgiving.

With an average weight of males being around 23 lbs, turkeys are some of the largest birds found in the Americas. The record for the largest wild turkey ever caught is a tad over 37 lbs, which is a truly massive bird. Male turkeys, known as “Toms,” head a harem of females and will mate with several females per season. Occasionally, a pair of males will be found within a harem, usually comprised of 8-10 hens, but they are often related, thus ensuring their gene pool stays strong. To attract females, males will fluff up their feathers, raise and spread their tail feathers, change their head colors, and strut around while calling out to females. After mating the females lay between 10 and 14 eggs in shallow nests on the ground. Toms are absent from the family picture at this point, but the females will defend the nest for about a month, at which time the eggs will hatch. Male turkeys will spar over potential mates and to defend their harem.

Toms are also known to defend their territory from anything they deem a threat, including small children playing in the woods of Eureka, Missouri in the 1990s, aka me and my childhood friend, Jacob. We would have been 5 or 6, playing around in the woods that surrounded his house as we often did. We heard the gobble, stopped looking for toads, and raised up to see a male turkey with its feathers spread just like those on all my grandma Gerry’s Thanksgiving decorations. Before we knew it, the turkey was charging us, and we ran screaming while hopping over fallen trees and logs until we made it back to his house. This event happened after seeing Jurassic Park, and given our small stature and the fact that turkeys are about 4 ft in height, it felt like a real-life Velociraptor Encounter. But despite the fear and nightmares of that event (I still wake up in cold sweats to the faint sound of gobbling), the fact that I have encountered multiple wild turkeys is a testament to conservation efforts. In the 1700s, it was estimated that there were over 10 million wild turkeys within the United States alone. Due to overhunting (really their fault for being so tasty), the wild turkey population comprised only 30,000 individuals by the 1930s. Conservationists captured turkeys from areas where they were more common and released them in areas where they once had a presence. By creating certain seasons for legal turkey hunting, the bird was saved and brought back from the brink of extinction. It is estimated that there are now roughly 7 million turkeys in the wild.

Wild turkeys play an important role in the ecosystem by providing food for a wide array of predators and omnivores alike. Wild turkeys are very fond of acorns but also eat insects, reptiles, wild fruits, grass seeds, and many other grains. During the day, wild turkeys can be found foraging for their favorite foods, but by night, they seek the safety of the canopy. Yes, some of you may not know this, but turkeys are actually great at flying, reaching up to 60 mph while in flight. I remember the first time I saw turkeys flying along the side of a highway, and it was a very surreal sight as they seemed too big to fly, but there they were, clearing the road and heading to an open field. Despite their flight speed and the ability to run 25 mph, the wild turkey has not been able to escape our diet. It appears that 20 million years of evolution makes for one delicious bird. I hope you all have an amazing Thanksgiving, and may your homes not be haunted by a poultry-geist.

References:

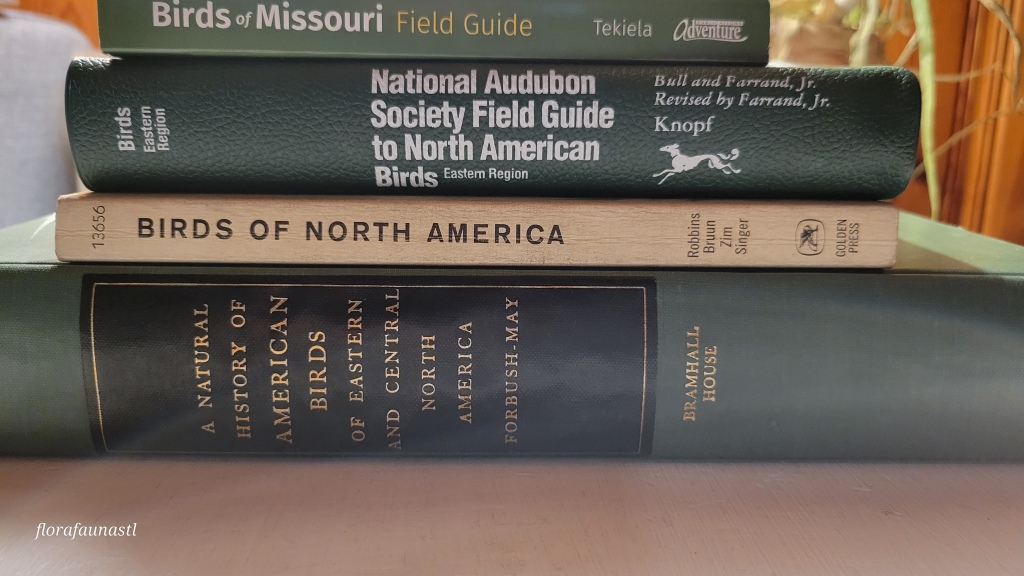

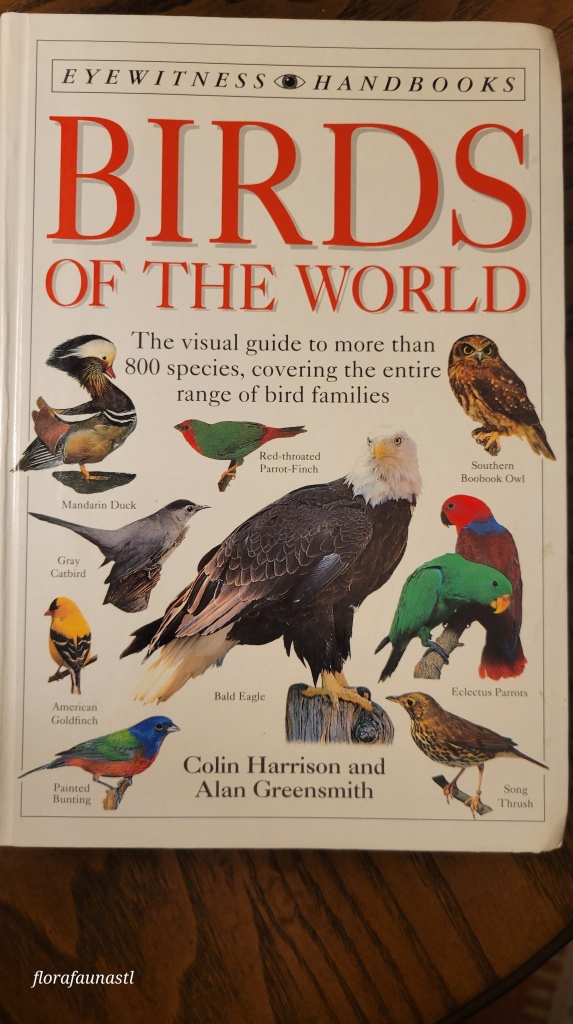

Harrison, C., Greensmith, A., (1993), Birds of the World, Dowling Kindersley, Inc., 95 Madison Avenue, New York, New York

Tekiela, S., (2021), Birds of Missouri Field Guide, Adventure Publications, Cambridge, Minnesota

Forbush,E. H., May, J., B., (1955) , A Natural History of American Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Bramhall House, New York

Bull, J., Farrand, J. Jr, (1996), National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Alfread A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Robbins, C.S., Bruun, B. and Singer, A. (1966), A Guide To Field Identification Birds of North America, Golden Press, New York

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/wild-turkey

Leave a comment