Halloween has long been associated with ghosts, werewolves, vampires, the undead, and many other creatures of the night. In film and literature, these creatures can be found lurking in the shadows of their local cemetery. Some of them are in search of blood while others have unresolved sufferings that won’t allow for peace, even in death. We all know (I’m fairly confident) that these monsters, don’t really lurk in cemeteries, but how many of us are aware that cemeteries are home to some fascinating real-life creatures that can live to be thousands of years old? Creatures that aren’t quite plants but aren’t quite animals either. Organisms, that like the other denizens of the graveyard, have a foot in two worlds.

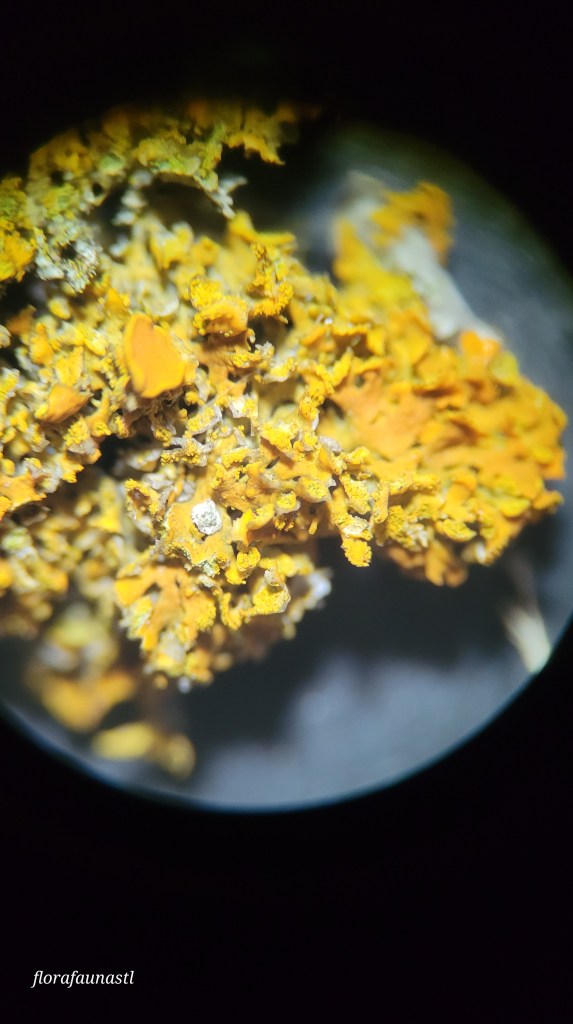

Clinging to the statues and headstones of the graveyard is none other than one of the Xanthoria Lichens, more commonly known as Sunburst Lichen. It is worth noting that there are estimated to be at least 20,000 species of lichen, with North America being home to more than 3,000 species. The professionals who study lichen also believe that there are many sub-species that have yet to be identified. Through my research and asking around on some mycology forums, I believe this is Xanthoria parietina, but please do not hold me to that exact species. For the purpose of this article, though, which will be very high-level, we won’t need to pin down an exact species.

Lichens are not an individual organism and are instead a composite organism. They are a combination of fungus, algae, and/or cyanobacteria, and potentially yeast, working in a symbiotic relationship. Fungi are unable to photosynthesize like plants and absorb their nutrients from their environment by releasing enzymes to break down decaying matter. Algae, on the other hand, can photosynthesize but are not classified as plants since they lack roots, leaves, and stems. Algae is a protist and belongs to the unique kingdom Protista, which is full of fascinating organisms. Lastly, cyanobacteria are microscopic bacteria that are also capable of photosynthesis and have been on Earth for a staggering 2.1 billion years! Before I go further into this Frankenstein of an organism, I want to be sure we all know that photosynthesis is the transformation of light, water, and carbon dioxide into sugar (energy) and oxygen. (I’m simplifying the process, but you get the gist.)

Based on fossil records, at least 400 million years ago, these organisms came together and figured out that if they bond together, they can survive and thrive in places others cannot. They are one of the most widespread life forms existing on every continent, (yes even Antarctica) and in every environment from mountains to deserts to, well, the local cemetery. Each organism in the lichen plays an integral role. The fungus forms the lichens’ structure and provides protection from the elements to the algae and/or cyanobacteria. In return, the algae and/or cyanobacteria provide meals/energy for the fungus via photosynthesis. The lichen often becomes interwoven to the extent that it barely resembles what the individual organisms look like and takes on unique forms of its own. Under a microscope, we can see in more detail where the fungus is in relation to the algae; the small green specks are the algae, and the white threads are part of the fungus.

We can also see that the lichen possesses apothecia, which is the cup-shaped structure of the fungus. The apothecia bears the spore sacs which are called asci. These spores, which are created by the fusion of gametes (sperm and ova) inside the tissue of the apothecia, will need to quickly find algae or cyanobacteria to bind to, or they will die off. Keep in mind that even lichen within the same family group do not reproduce the same way; some may use vegetative reproduction, but with the appearance of apothecia, we can deduce that this species of Xanthoria reproduces via spores. There are also a few different ways to define lichen based on how they adhere to their substrate. Those scale-like lichen that adhere very closely to their substrate are called crustaceous; those that adhere less closely and possess more leaf-like structures are called foliose; and lastly, those that branch out and are hang freely are called fruiticose. Xanthoria parietina is a foliage lichen and thus is attached to its substrate more loosely.

It’s easy to look at these gravestones, see this lichen (which most confuse with moss), and think about death and decay, but I assure you lichens are actually quite the opposite. You see, lichens are known as a pioneer species, meaning that they are some of the first organisms to inhabit what most creatures would consider uninhabitable land. They are often some of the first life forms found on volcanic rock, and they actually help to create soil for other plants, although this takes a very long time. Lichens slowly break down rock by releasing oxalic acid, as well they will find their way into rock cracks and expand and contract with the weather, which further breaks down the rock. Lichens also play a role in the food chain with certain species being eaten by herbivores, insects, and can even be found in some human cuisines. I would say, though, it’s probably best to avoid munching on a lichen snack when visiting the graveyard, as some species are toxic due to the acids they produce and could potentially convert you to a full-time graveyard dweller. Although lichens can also be found on trees and other plants, they do not pose a health threat to them and are simply living on them. The world of lichens extends much deeper and is much more complex. If you are truly interested in learning more, there are several books and websites dedicated to them.

It may seem macabre, but one of the reasons I chose to visit the graveyard (besides for the Halloween post) is because graveyards actually provide a safe haven for lichens. They are often less polluted due to their distance from town centers and lack of (live) human interaction, which allows for lichens to thrive. Lichens can live to be thousands of years old, with some of the oldest specimens being around 9,000 years old. It is also believed that many lichens start to form the moment that gravestones are erected. This means that some of the lichens in these photos could be from the late 1800s. To me, there is something kind of fun and peaceful about lichens growing in cemeteries. It is a little friend for the ghosts and a reminder that even in places of death, life will thrive.

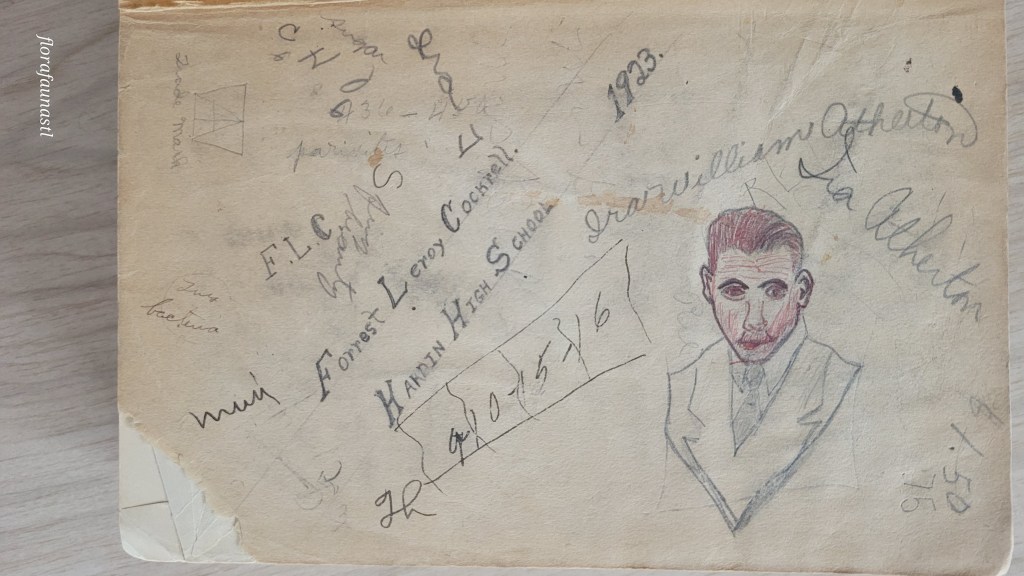

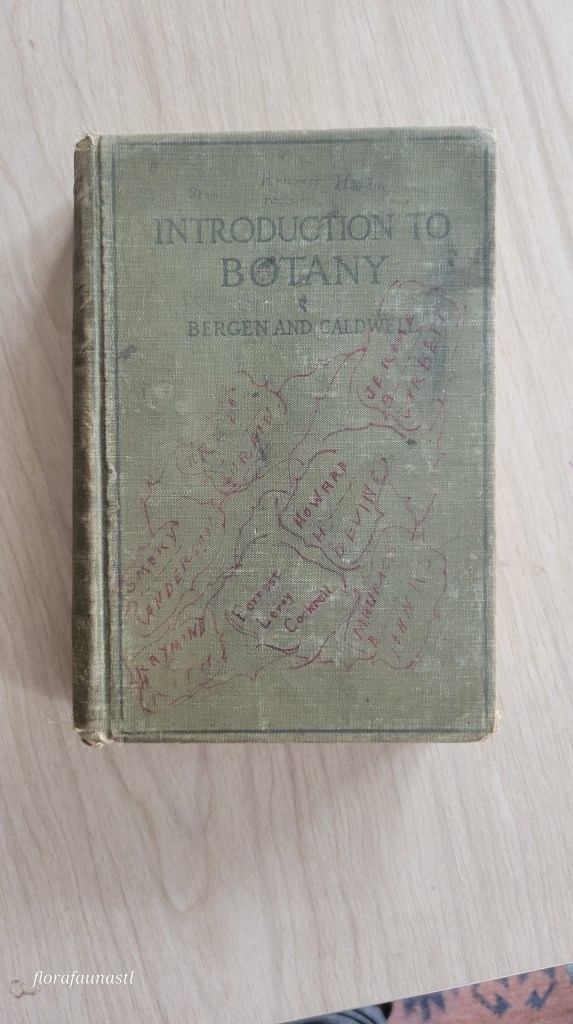

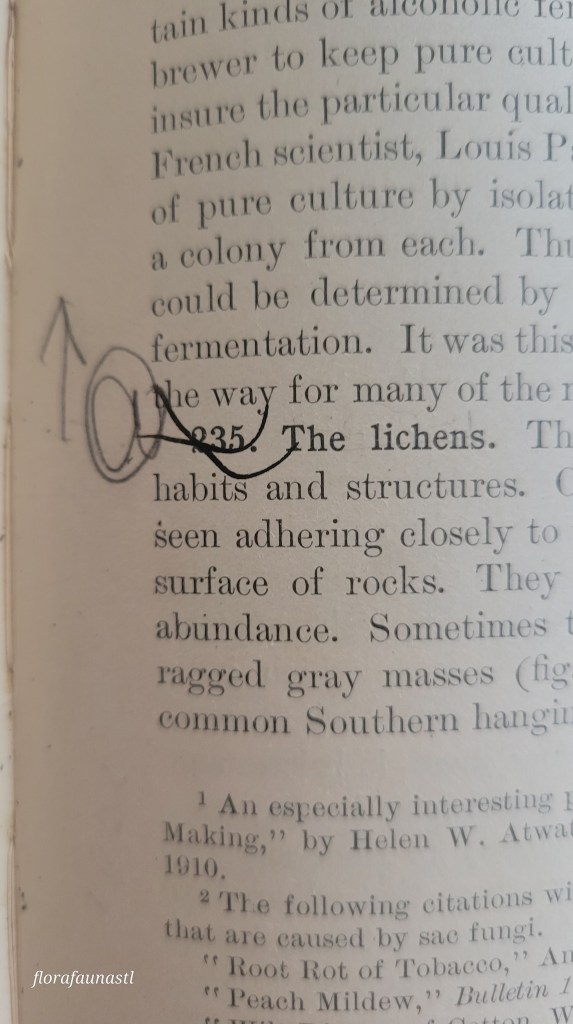

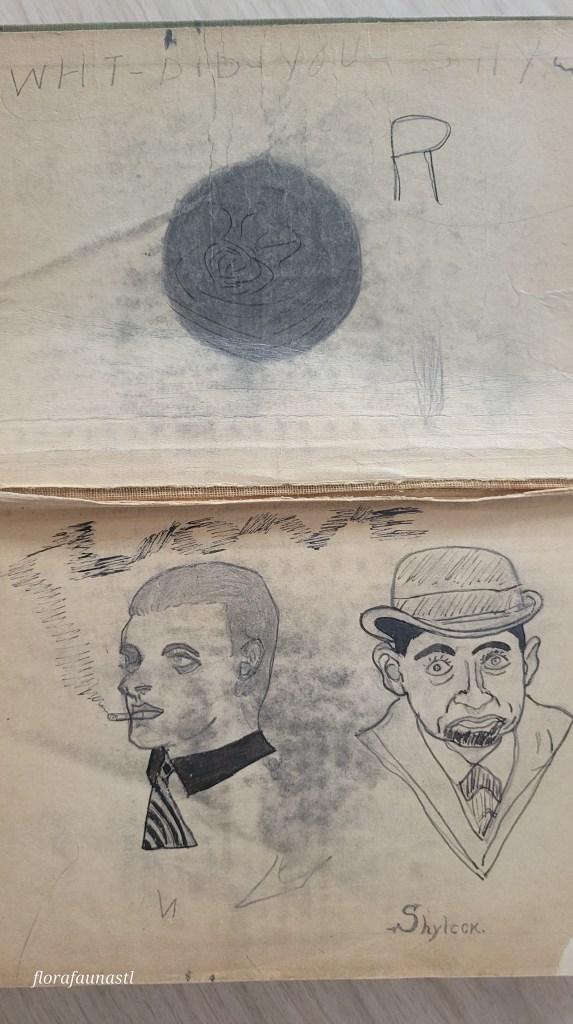

I would also like to talk briefly about the help I had with my research from beyond the grave. No, it isn’t a real ghost, but he was a real person. I have an old book from 1914 titled “Introduction To Botany,” and it must have been used in high school. The owner of the book in 1923 was a young man named Forrest Leroy Cockrell, and he attended Hardin High School in Illinois. I came across the book almost a decade ago at Goodwill of all places, and it has been a foundational starting point for much of my botany research. Forrest left notes, drawings, and doodles in the book and even highlighted certain areas; lichens happen to be one of them.

A while back I searched through a genealogy website and I was able to locate Forrest, he passed away in 2004 at the age of 96. Despite this, he feels very much alive, and I will often read a section of the book, see his notes, and mumble a few words to him or chuckle at some of the things he wrote. I feel to some extent that Forrest and I are intertwined through this book, although not nearly as intertwined as the organisms that form lichens. I am not ending on this note because I want us to be disheartened, but rather because it is a reminder that we all have much more of an impact than we often realize. We are all so interconnected in ways that we can barely comprehend, much like lichens, and I think it is important that we remember that. I hope you all have a fun and happy HALLOWEEN, and of course, happy birthday to my father.

References:

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/orange-sunburst-lichens-xanthoria-lichens

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/lichens

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_lichen_terms

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xanthoria_parietina

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xanthoria

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/immortal-lichen-growing-in-cemeteries

Leave a comment