Earlier this summer we had a privacy fence put in, which meant the old chain link fence and all the honeysuckle that had grown to encompass the fence had to be removed. I was saddened by the destruction this would cause to the ecosystem of my yard. Sure, honeysuckle is highly invasive, but these massive bushes had provided housing for hundreds of little birds and countless insects. It was always buzzing with the sounds of pollinators zipping from flower to flower; bees, wasps, hummingbirds, hummingbird moths, etc. The smell of the honeysuckle had come to be a harbinger of summer as the whole yard would have a faint and sweet smell from the abundance of flowers. But alas, all good things must come to an end, and sometimes the consequences of which can be fruitful.

As mentioned in an earlier post about Eastern Nightshade, I let areas around the fence grow untouched to see what nature would bring to fill the new void. One of the most prolific of these void fillers was a peculiar-looking plant. At first, the serrated, irregularly toothed leaves led me to believe that this may be dandelion, or some kind of wild lettuce. But the plant continued to grow taller and taller, eventually surpassing my 5’10 height. This tall, uniformly green plant began to produce panicles at the uppermost stems. Panicles are loose clusters of fruits or flowers. These odorless flowers looked almost like dandelions before they opened up and revealed their golden yellow flower; only these never opened up.

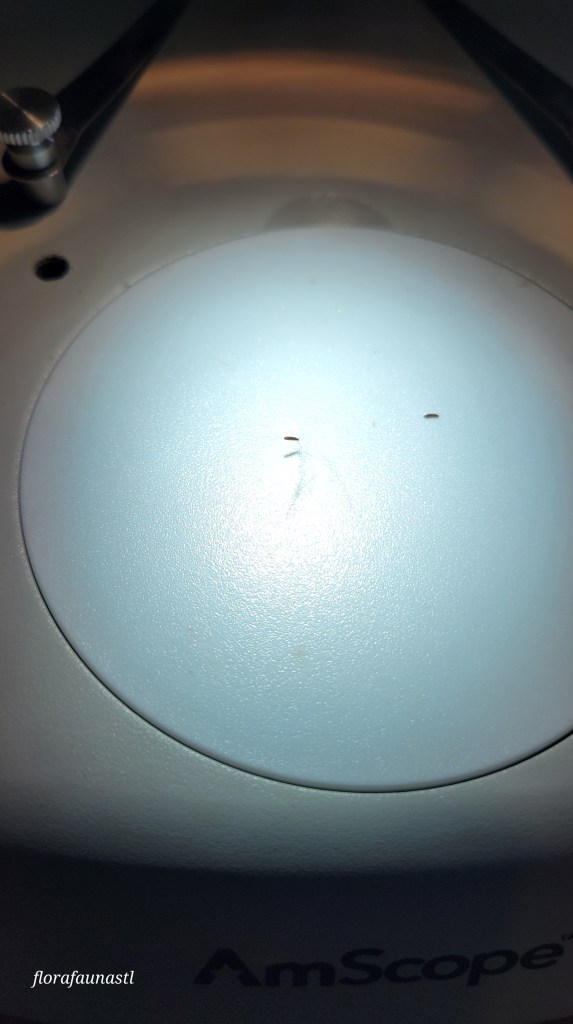

Instead, this flowerhead houses (totally) tubular florets with whitish-yellow corollas (petals) that barely protrude from the cylindrical bracts/phyllaries. Phyllaries are the green leaf-like structures that surround the base of flowers and/or fruit to provide protection. Earlier I stated that when I first saw this plant growing, I thought maybe it was a dandelion. After allowing it to grow, it clearly was not a dandelion unless the ooze from TGRI the second Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle movie somehow contaminated my yard. Although my initial guess as to what this fledgling plant may be was wrong, I was not too far off. This native annual plant is Erechtites hieraciifolius (commonly known as Pilewort, Fireweed, or Burnweed) and is a member of the daisy family (Asteraceae), as are dandelions. These distant cousins share a few other similarities besides leaf structure, though.

The main and most easily visible similarity being the way they spread their achenes (dry one-seeded fruit) via white fibrous hairs that float off in the wind. That’s right, this whole time us laymen have called those floating tiny “seeds” on dandelions “seeds,” but they are, in fact, fruit. I also learned while researching achenes that strawberry “seeds” are actually achenes, and therefore the fruit that houses the actual seed. The lush and tasty red part we consider the fruit is really just a fleshy receptacle (base part of the flower), and botanists actually refer to strawberries as pseudocarp or false fruit. Have fun with that extremely useful fun fact the next time you end up at trivia night or bring it up any time you serve fruit salad! Burnweed is also edible but has a very strong and often unfavorable taste; it also has a pungent smell if you break the stems or crush the leaves. The plant does have other uses, though; it has been used historically to treat rashes, heart conditions, diarrhea, and can be used to create blue dye.

Let’s take ourselves out of the picture, though, and ask what this plant does for nature? What or who does it benefit? Well, for starters, it provides nectar for many species of the hymenoptera family (bees and wasps), as well as butterflies. But what I think is the most fascinating about this plant is its status as a pioneer plant. When there is disturbed ground (like near my fence) or a forest fire has blazed through an area, burnweed is often one of the first plants to sprout, hence the names Burnweed and Fireweed. It can survive in rocky environments with certain degrees of drought but prefers moist soils. Burnweed will flourish quickly in these disturbed areas but is easily overcome by competition from other plants. However, burnweed plays a few vital roles underground too.

First, the quickly growing burnweed roots have the ability to help prevent soil erosion as they are fairly dense. Burnweed also helps to establish and plays a huge part in the mycorrhizal network, which is like a nutrient and water trade system between fungi and plants, essentially enriching the soil for other plants to thrive. Back above ground, burnweed also has the ability to absorb nitrogen dioxide from the atmosphere, to the extent that about 10% of the plant’s nitrogen comes from this harmful pollutant. This makes burnweed a plant that is welcomed by many in urban environments as it is a natural way to help rid our air of pollution.

Now, I know this plant got here via evolution and found its niche in burned down fields and forests, BUT Burnweed is essentially a selfless first responder of the natural world. I let the 5 burnweed plants in my yard grow and watched their achenes float away in the winds towards the end of summer. I was pleased to know that they are going out to find areas devoid of life and will help to bring nature back. Eventually, a heavy storm blew the shallow rooted plant down, and I had to dispose of them, but not before putting that rich soil from the root ball into my compost! This is one of those species that really helps to visualize how perfectly balanced nature really is.

References:

https://extension.psu.edu/american-burnweed-erechtites-hieraciifolius/

https://weedid.missouri.edu/weedinfo.cfm?weed_id=112

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erechtites_hieraciifolius

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phyllary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achene

https://www.missouriplants.com/Erechtites_hieraciifolius_page.html

Leave a comment