When I was 5.5 years old, we lived in Washington, Missouri, directly across from the school I went to for kindergarten. Nestled behind and next to that school was a creek that hosted many adventures for me and the other children in the neighborhood. I could see it from my bedroom window, just beyond the weeping willow that called our front yard home. I would look out at night from my second story window and see the lightning bugs flashing around the creek, while the sounds of cicadas and frogs would build to a climax before suddenly falling silent. After a brief pause, their competitive singing would start again. I was excited for any and every chance I got to go play in the creek, as you never knew what you would find. We would see minnows, insects, crawdads, a variety of amphibians, snakes, and the list goes on. Some parts of the creek were deeper than others, and we knew to steer clear of those areas. Not only could you get tangled up in fallen trees, but the water was muddy and visibility was null. At that age, the number of monsters that could be lurking below the calm muddy surface, waiting to take children to their watery graves, were numerous.

That rainy summer, I would discover what was in the depths of that creek. In fact, the whole neighborhood was about to find out. The year was 1993, and the Great Flood was in full effect. The Great Flood of 1993 was massive; it ranged across 9 states, covered 400,000 square miles, destroyed thousands of homes, took the lives of at least 50 people, and caused billions of dollars worth of damage, north of $25 billion in today’s dollars to be more precise. Extreme weather conditions, excessive amounts of rainfall coupled with above-normal soil moisture due to lower temperatures that summer, set the stage for the devastation. Some areas in the Midwest had rainfall up to 4ft, and many areas had twice as many rainy days than they would normally have. It was utter mayhem and chaos, and as a 5.5-year-old, you don’t grasp the reality, the impact that has on people’s lives, not like you do as an adult. I knew it was bad, I knew the creek that we played in had now swallowed the bottom floor of my school and the houses across the street. I was out there with my parents stacking sandbags in a futile attempt at halting the creek from coming any closer, all while the rain continued to fall and the water got higher and higher. The whole community, people from around the state, had all gathered to aid in the laborious task of building a wall with sandbags. But it was because of this catastrophic event that I saw it, the monster that lived in the bottom of the creek.

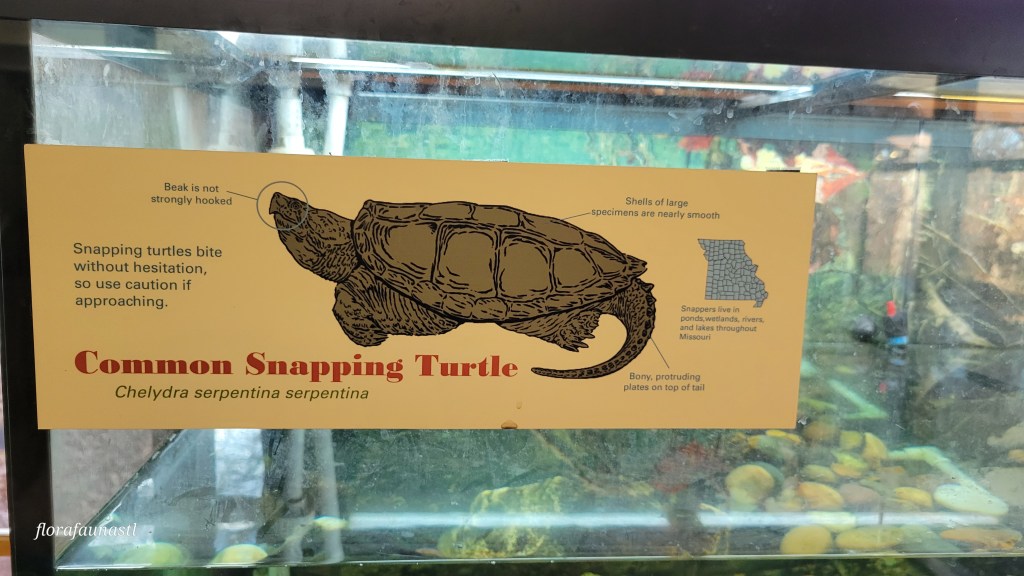

It had been found by one of the neighborhood folks who was tasked with stacking sandbags. Boy, was it a monster, especially to a 5.5-year-old who had never seen anything like it, at least not face to face. All the kids gawked as this man pulled an Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) through the ankle-deep water, perched atop a red Radio-Flyer wagon. It couldn’t actually fit in the wagon; it was wider than the wagon itself and sat perilously on the edges as the man and his buddies dragged it along. The snapping turtle has a very distinctive large head that ends in an extremely sharp beak, and this one kept its mouth wide open while it’s tiny black eyes rotated around scoping the crowd out.

I remember one of the fathers yelling at us to keep our hands away, as it would take our fingers clean off. Great advice that has always stuck with me, and this turns out to actually be true! They have razor-sharp beaks and a bite force up to 1,000 PSI. To put this in perspective, a Pit bull’s bite force is around 235 PSI. For those not in the know, PSI is short for pounds per square inch. Back to 1993 though, I stood there in awe as this monster of the creek was wheeled past. We locked eyes, and I was split between fear and curiosity. I had to learn more about this monster of the creek, and learn I did!

So let’s do as an Alligator Snapping Turtle would and dive right in to the facts. These nocturnal predatory turtles are masters of aggressive mimicry, luring fish and other prey in by lashing around their vermiform (worm-like in appearance) tongue. They will lie in wait until prey comes close enough for it to lash out and gobble them up. They are opportunistic and will eat most anything that will fit in their mouth. They have been observed eating fish, crawdads, turtles, clams, snakes, frogs, toads, plants, waterfowl, muskrat, baby alligators, raccoons, squirrels, opossums, rodents, etc. As you can see by the food on the menu, really anything goes, so long as they can chomp down on it. Although the animals towards the end of the list are not as common, if the Alligator Snapping Turtle is big enough, and sees the opportunity, it takes it. They will also scrounge for carrion of any kind to satisfy their appetite.

Being turtles, they are fairly slow on land, topping out around 2.5 mph; in the water, they can swim at about 10 mph. So how can they catch prey, you ask? Well, they clamp their jaws shut at around 200 mph! Coming full circle here, you can see this is an animal that can easily take your fingers, toes, or even more clean off you. But before you get too anxious and vow to never wade in a creek or swim in a lake again, please know this rarely happens. Most instances of humans being bitten by an Alligator Snapping Turtle have occurred when these turtles have to defend themselves, and more often than not, that occurs when the turtles are on land.

Alligator Snapping Turtles are predominantly aquatic turtles and rarely leave their watery sanctuary. They are most often seen surfacing for air, which they do every 45 minutes or so before retreating back to the depths. In fact they don’t even leave the water to bask in the sun, they simply swim closer to the surface and float. There are few reasons why these turtles would even be on land to begin with, but the main reason is to lay eggs.

From May to June, females will venture away from the water and lay an average of 30 soft white leathery eggs, although there have been reports of up to 3 times that amount found in one nest. The nests are usually dug about 150ft away from the water so that flooding of the nest is less likely to occur. As with many reptiles, the sex of the eggs is dependent upon the temperature of the nest. This is known as temperature-dependent sex determination. Hotter temperatures produce females, while cooler temperatures produce males, there can be instances of mixed-sex nests if the temperature falls between certain temperatures as well. Incubation takes anywhere from 11 to 16 weeks, after which the babies emerge and make a mad dash for the water.

Alligator Snapping Turtles grow quickly and can reach massive sizes. They are, in fact, the largest freshwater turtles in the world. The average weight for these snappers is between 35 to 150 pounds, with their carapace (shell) reaching lengths of 15 to 26 inches. These are already massive weights, but the outliers are more impressive, with a record weight of 316 pounds and a length of 31 inches. They are sexually dimorphic, with females being the larger of the sexes. Alligator Snapping Turtles invoke thoughts of dinosaurs with their serrated shells, displaying three definitive rows running the length of their shells. They sport long, gnarly-looking claws on their webbed feet. To top it off, they have abnormally long tails for turtles. They range from brown to gray in color, which helps them to camouflage into their natural environment. Native to North America, they can be found inhabiting lakes, ponds, rivers, and creeks ranging from the Florida panhandle, west to the easternmost edge of Texas and as far north as Illinois.

Their numbers have declined in recent years, and they are now listed as a species of concern by the Missouri Department of Conservation. Although they are native to North America, there is an invasive population that can be found in South Africa. Around the city, you can catch a glimpse of these beautiful turtles in local waterways and ponds. I have spotted one in Forest Park and at a few of our conservation areas within the Greater St. Louis region. As well, you can see them in zoos and at Powder Valley Nature Center, where these photos were taken. I will never know what happened to the first one of these awesome turtles I saw, but I will never forget that experience, that rush of excitement. It was one shell of a first encounter and a memory I will always cherish.

References:

Behler, J. L. and King, F. W., (1979), The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., New York.

Johnson, R., Tom,(2000), The Amphibians and Reptiles of Missouri (2nd edition), Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri

Leave a comment