As I was walking past our living room a few nights back, I noticed an Opossum in the front yard. Like any normal human, I ran for my phone and darted outside to get a picture. The Opossums must have seen me through the window though because by the time I rounded the side of the porch, they were nowhere to be found. I turned the flashlight on to look in the bushes and see if maybe they found a quick hiding spot. To my disappointment, my date with North America’s only Marsupial wasn’t happening tonight.

I came inside defeated and went to the bathroom to brush my teeth and get ready for bed. As I began scrubbing away at my pearly whites in the mirror, I saw something move just out of view, from my shoulder towards my back. Startled, I turned around to look at my back in the mirror and there was nothing there. I looked around on the floor, the counter, and didn’t see anything. All of a sudden, I saw it barreling towards me from the shower curtain. It was heading right for me, and I knew it was going to gouge one of my eyes out, so I did what any normal person would do: threw my arms over my face and screamed like an old B-Movie actress.

That must have done the trick because the Junonia Coenia, more commonly called the Common Buckeye Butterfly, landed on the wall. My eyes had been spared and left to gaze upon the four stylish orange, purpleish-blue, black, and tan eye spots of this impressive 2 1/2 inch butterfly. The body of the Common Buckeye is mostly brown, with the exception of two dashing orange marks on the forewing and creme white bands as well. The butterfly angrily opened and closed its wings as it sat perched on the wall before making a bold attempt to take my eyes out again, but this time I called its bluff and pulled my phone out of my pocket to get some pictures.

Now that the camera was rolling, its aggression died down significantly, and it posed for the camera. The opening and closing of the butterfly’s wings continued, and I assumed it was to intimidate me, but learned after doing some research that they actually do this to warm themselves up. This poor guy must have been resting outside on a cold October night, saw the light from my phone, and made a mad dash for the light to get warmth.

The Common Buckeye butterfly can be found throughout most of North America from spring through fall. They are found in a wide variety of habitats from open fields and gardens to roadsides and weed lots. They flutter around feasting on a variety of flowers ranging from milkweed to mint and are fond of yellow and red flowers, with a preference for the former as they age. This tells us that they are visual feeders more so than going by scent. They are also attracted to old fruit, and as we all know, old fruit ferments. Personally, I wouldn’t have wanted to run into this tough guy after a night of old fruit imbibing; he may not have cooled down for the camera after such debauchery.

Speaking of cooling down, this species is not able to withstand the winters of the northern states, and they either die out or retreat back to the southern regions of the United States between September and October, where they overwinter. They do, however, have several broods between spring and fall and will continue mating and laying eggs in the south, where populations can be found year-round. The males wait for females to approach them, and they hang out near the ground and are apparently territorial, chasing away not only other males but other insects as well. The females will lay small green eggs on the leaves of their host plants, which will hatch within two weeks.

Now, this is where the story really gets interesting. Females look for plants that have high levels of iridoid glycosides. These plants include plantains, snapdragons, and toadflax, to name a few. They seek these plants out because the caterpillars chow down on them, and once ingested, these toxic chemicals build up and offer a defense against predators such as ants, wasps, and birds. There are some catches, though. The chemicals interact with the gut, making them always feel hungry, which causes them to be voracious eaters. In addition, high concentrations of these chemicals can affect the immune system and leave them susceptible to parasites. For reference, the caterpillars are bluish-black with orangish-yellow spots and shiny blue spikes. The spikes are a warning to predators, but don’t worry, they are not toxic to humans, although I would refrain from eating them.

They are in the caterpillar phase of life for two to four weeks, the timeframe being determined by the abundance of food. Once the caterpillars are full and ready to transform, they build their chrysalis by hanging from a branch or another horizontal structure. They remain in the chrysalis for one to two weeks before emerging as an adult butterfly. Once adults, they live for about twenty days. Throughout all stages of their lives, they are solitary creatures but can sometimes be seen in gatherings around favorite food sources.

As adults, they face predation from birds and insects and, of course, the race against the cold if they are in the northern parts of the United States. After getting some pictures and video, I was able to convince my rowdy house guest to venture back outside. He fluttered over to the blowmold ghost I inherited from my grandmother and hung there for a while. I am sure the warmth comforted him for a good portion of the night. With the temperatures dropping quickly this year, I presume he never made it back south to warmer weather, but at least he reached adulthood and presumably passed his genes on to a few broods of young Buckeye Butterflies. One can only hope they are not nearly as aggressive as their father. For clarification, these butterflies are harmless and essential pollinators; no one has lost an eye to them…that I know of.

References:

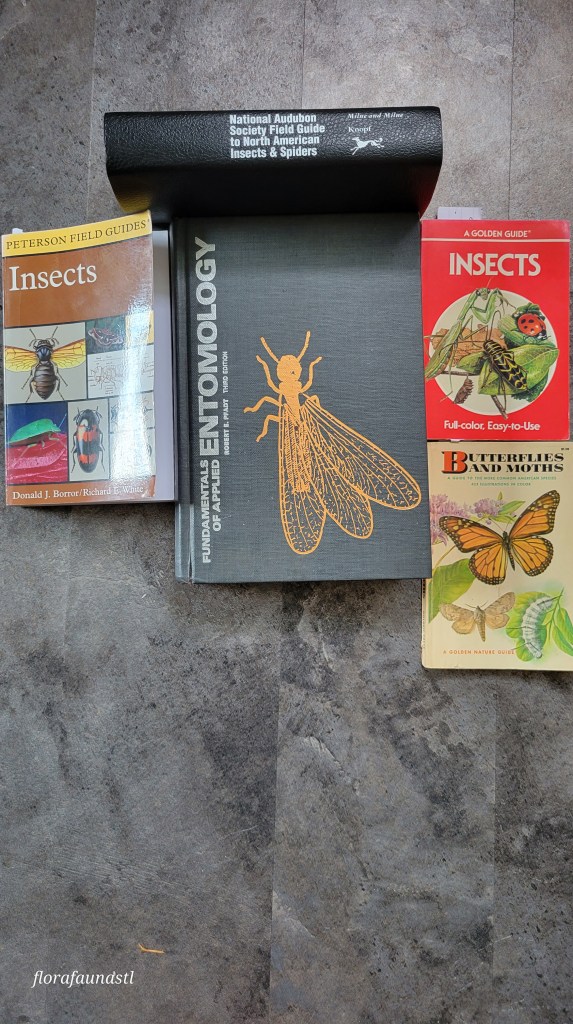

Milne, Lorus and Margery. (1980), The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York

Zim, H.S. and Cottam, C. (2001), Insects, St. Martin’s Press, New York

Borror, D. J. and White, R. E., (1970), Peterson Field Guides: Insects, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York

Pfadt, R. E., ( 1978), Fundamentals of Applied Entomology (3rd edition), Macmillan Publishing Co., INC., New York

Mitchell, R.T. and Zim, H. S., (1964), Butterflies and Moths A Guide To The More Common American Species, Golden Press, New York.

Leave a comment