In 2015, my wife and I got married and decided on the Lake of the Ozarks for our honeymoon. We wanted somewhere that was not only romantic but fairly close to home for quick future revisits. We settled on Lodge of the Four Seasons as they have a beautiful view of the lake and lots of amenities ranging from fine dining, pools, a game room, massage parlor, and a theater.

We spent much of our time out exploring and taking in the picturesque sunsets over the lake. There was plenty of wildlife around us, but one critter stood, quite literally, out from the rest. This was none other than the Marmota monax, more commonly known as a groundhog, whistle-pig, land beaver, mouse bear, or woodchuck depending on your neck of the woods. They range from the east coast to the Midwest and north into Canada.

Their natural range spread along with European settlers who cleared forests and made more meadows and grasslands, which are favorable for the woodchuck. This new favorable real estate also increased the woodchuck population, which prior to settlers was fairly scarce. The name for this animal varies by region; here in the Midwest, we tend to refer to them as woodchucks but in Appalachia, they are commonly called whistle-pigs, due to the sound they make when warning others of danger.

I’d overheard some of the other guests at the Lodge of the Four Seasons calling them groundhogs. Our honeymoon was not my first encounter with the largest member of the squirrel family, but it is by far my fondest. Yes, you read that correctly, they belong to the family Sciuridae. And like squirrels they can climb trees, although this is a fairly rare sight.

During our honeymoon, my wife and I played a game of “who can spot the most woodchucks”, looking for them along the edges of the lake, forests, and roadsides. I can’t recall the final score, but I can confirm I was a close second place for most woodchucks spotted. Fast forward to the present time and we still see them out and about in St. Louis. I assume there are quite a few of us who spot them along River Des Peres, in Forest Park, in the grass along the sides of roads (hopefully alive and well), and in our yards.

Given their grayish-brown fur and large size (16-27 inches in length and weighing up to 14 pounds), they are sometimes mistaken for beavers, especially when seen near or in waterways, as they are fairly good swimmers. Although they do not build dams like beavers, they do build, or should I say carve out, a rather impressive home for themselves. With the ability to move over 700 pounds of subsoil in a single day, the woodchuck will make elaborate homes, featuring multiple entrances, rest chambers, nursing chambers, and even bathroom chambers.

They can build their homes in grasslands, hillsides (preferably rocky), and stream banks; often placing the main entrance below large rocks or tree stumps. The woodchuck has short, powerful legs that are perfectly adapted for digging through dirt and living underground. They also sport valvular ears and have a valvular nose, meaning they have the ability to close those orifices to prevent dirt from entering. They move dirt out of their chambers and tunnels by pushing with their head and also carrying the dirt out via their mouth. It is not uncommon to see a few feet of earth piled up outside the main entrance, sometimes nearing heights of five feet. They will often use this mound as an observation deck, relaxation spot for sunny days, or sometimes as a bathroom.

The entrance to their underground dwelling is usually about a foot or so in diameter and gets narrower the farther it goes. These tunnels may stretch for 10 to 45 feet before leading to the main nesting chamber. It is not uncommon to find multiple chambers for resting and sleeping, chambers for the bathroom, faux tunnels, nursing chambers, and up to five entrances, although typically there are only two. They keep their homes astonishingly clean, adding new layers of dirt to the bathroom chamber to cover waste and using leaves and grasses to make beds for themselves. Their home range is typically between a quarter and a half mile in diameter, and they defend their homes from each other depending on the sex. Males will often share territory (not home) with a female woodchuck or two, same-sex territory is not shared, and males will defend their turf. Rarely is there more than one woodchuck in the home unless we are talking about mating or the rearing of young.

Before we cover the woodchuck mating rituals, though, let’s start with the fascinating ability these animals have to hibernate. In late autumn when their food sources start to dwindle (they are fond of grasses, clover, alfalfa, apples, and pawpaws), they head for their resting chamber, seal it off with dirt, and go into hibernation. We all know that hibernation involves sleeping, and sure, they are dreaming of whatever woodchucks dream about, but there is so much more than meets the eye during this deep sleep. They slow their breathing down substantially, down to two to three breaths per minute. Their heart rate drops from roughly 80 bpm to 5 bpm, and their body temperature drops to 40°F, sometimes lower. Once in this state of hibernation, they are notoriously difficult to wake up. One story I read while researching woodchucks involved a curious woodchuck caretaker rolling their pet woodchuck around in front of the fire, and it still did not wake up for over an hour. Upon its awakening, it ran back to its box in the corner of the room and remained there until spring. (To address this now, woodchucks can apparently be semi-potty trained, but this story was from the late 1800s, so my guess is it is not the pet you really want in modern times. They can carry diseases like rabies and tularemia that can spread to humans and potentially be life-threatening. Admire from a distance and let them be free.)

In January, the first to awaken from this hibernation are the males, who will make their rounds to the females within its territory’s range. They invite themselves into their homes and spend some time with them, getting acquainted and making a good impression. After doing so, he will return back to his home and sleep a little longer. This highlights the male brain rather well. These guys have lost a quarter of their body weight hibernating and rather than looking for food…they are searching for woodchicks.

Once it is time for all woodchucks to come out of hibernation, typically in February, the males will visit the females again and spend a day or so with them, this time to mate. Once mating is complete, the male leaves the female and returns to his territory where he goes about his business of securing his territory, eating, cleaning, and pretending to be a tiny bear standing on two legs. The females, however, remain in their nursing chamber during their 32-day gestation period and give birth to litters ranging from 2-9 hairless, blind, and helpless woodchucks. What a life! In about a month, they will open their eyes, and within another two or three weeks, they will finally venture outside. Occasionally, males have been observed to help out with caring for the young once they have left the comfort of their mother’s burrow. By the middle of summer, the young will move out on their own and establish their territories.

Most woodchucks spend the majority of their days hanging out in their underground homes, with an average of only 3 hours outside per day. So the chances of seeing one are already fairly slim, but we still spot them around town fairly often. One has become somewhat of a family celebrity as the children shout out, “there’s the groundhog!” when they spot him as we drive by his usual spot.

I went out on my own to get some close-up pictures and investigate its territory. I observed at least three different woodchucks living along this particular stretch near one of the Great River Greenways and plenty of holes along the sides of the steep rocky riverbanks. It is much more of a waiting game to get some pictures as they will run, at 10 mph, back to their hole if they see you approaching. As I was venturing down one of the rocky sides of River Des Peres to get a photo, I had lost my footing on the loose gravel and started sliding down the steep side quickly. I ended up on my stomach and thankfully was able to get a hold of a large rock before the slipping got out of hand. While I was making my way back up in a crawling position, I had accidentally come face to face with a woodchuck preparing to leave one of its holes that I was not aware of until that moment. There I was, maybe two feet away from this shocked woodchuck who was startled and staring into my eyes with its pitch-black eyes before it turned and ran back into its home. I assume it decided not to gnaw my face off because I was already struggling to get back up the side of the rocky hill it easily climbs and was showing me mercy. I continued my journey back up the side of the hill and safely made it to stable ground. I backed off and waited for the woodchuck to emerge and was able to get some good photos.

Now, would he really have attacked me, you ask? Well, they can get aggressive. If threatened by predators, they will chatter their teeth while making a kind of grunting noise and may even charge and bite. Being a rodent, the teeth of woodchucks never stop growing and are extremely sharp, so being bitten by one would not be very pleasant. Human attacks are rare however, and they tend to reserve this aggression for the coyotes, foxes, owls, and other predators that may try to make a meal of them.

In nature, woodchucks play an important role in providing shelters for other animals. It is fairly common to find skunks, toads, snakes, badgers, and other critters living in some of the chambers within the woodchuck’s burrow as moocher roommates. Coyotes and foxes will also set up residency in abandoned woodchuck homes.

In terms of human interaction, if they are in your yard, they could pose some potential problems. Because of their extensive tunnels, if they get beneath structures, it could cause foundation issues. On farms, cows and farm equipment will sometimes fall into woodchuck homes, causing some expensive damages. Apart from these potential threats, and the raiding of our vegetable gardens, most groundhogs will live happily at a distance from us and just enjoy munching on our grasses. If you drive on our highways, near any parks or fields, chances are you have passed by one of these fascinating critters and may not have noticed. Keep an eye out for them and maybe play the “Woodchuck Spotting Game” to make car rides more exciting. However, one must be prepared to turn the car around sometimes to challenge a potential spotting point. A few contestants in our car have lost points due to a misidentified log.

References:

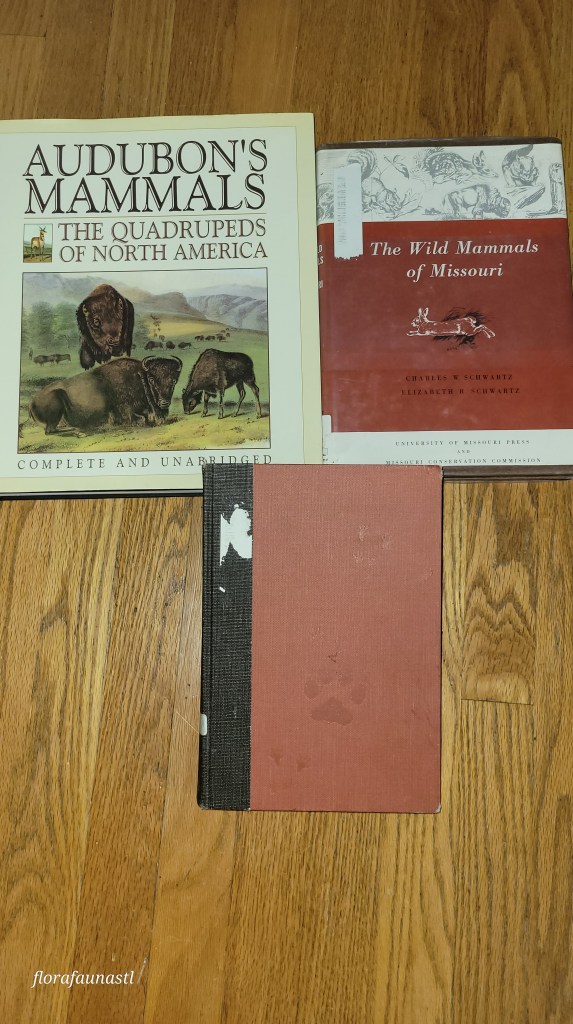

Shwartz, C. W. and Schwartz, E. R., THE Wild Mammals of Missouri, (1956), Smith-Grieves Co., Kansas City, Missouri

National Geographic Society, Wild Animals of North America, (1960), R.R Donnelley and Sons Co., Chicago

Audubon Society, Audubon’s Mammals: The Quadrupeds of North America, (2005), Wellfleet Press, Edison, New Jersey

Leave a comment