“We found at least twenty toads in here. They are everywhere!” exclaimed one of the amazing Boy Scouts who comes to help us clean out the neighborhood lily pond each spring. To be clear, he was not exaggerating. If anything, he was underreporting.

In 2020, I took over as the leader of the Lily Pond crew at Francis Park here in St. Louis Hills. My first year organizing the big clean-up, I noticed that there were toads everywhere in the dried-out pond. The rainwater and Bald Cypress debris create small pools of water that are shady and, importantly, fish-free. This is exactly the type of nursery that mother toads fawn over. The males are well aware of this. Walking by the pond on a spring evening, one will hear the loud rhythmic mating calls from all directions…and nothing else. With each big pile of leaves and sticks we shovel out, you are almost guaranteed at least one or two toads hiding out. Some still locked in their warm embrace, male toads latched onto the females and holding on until the eggs are laid, a move referred to as “amplexus”.

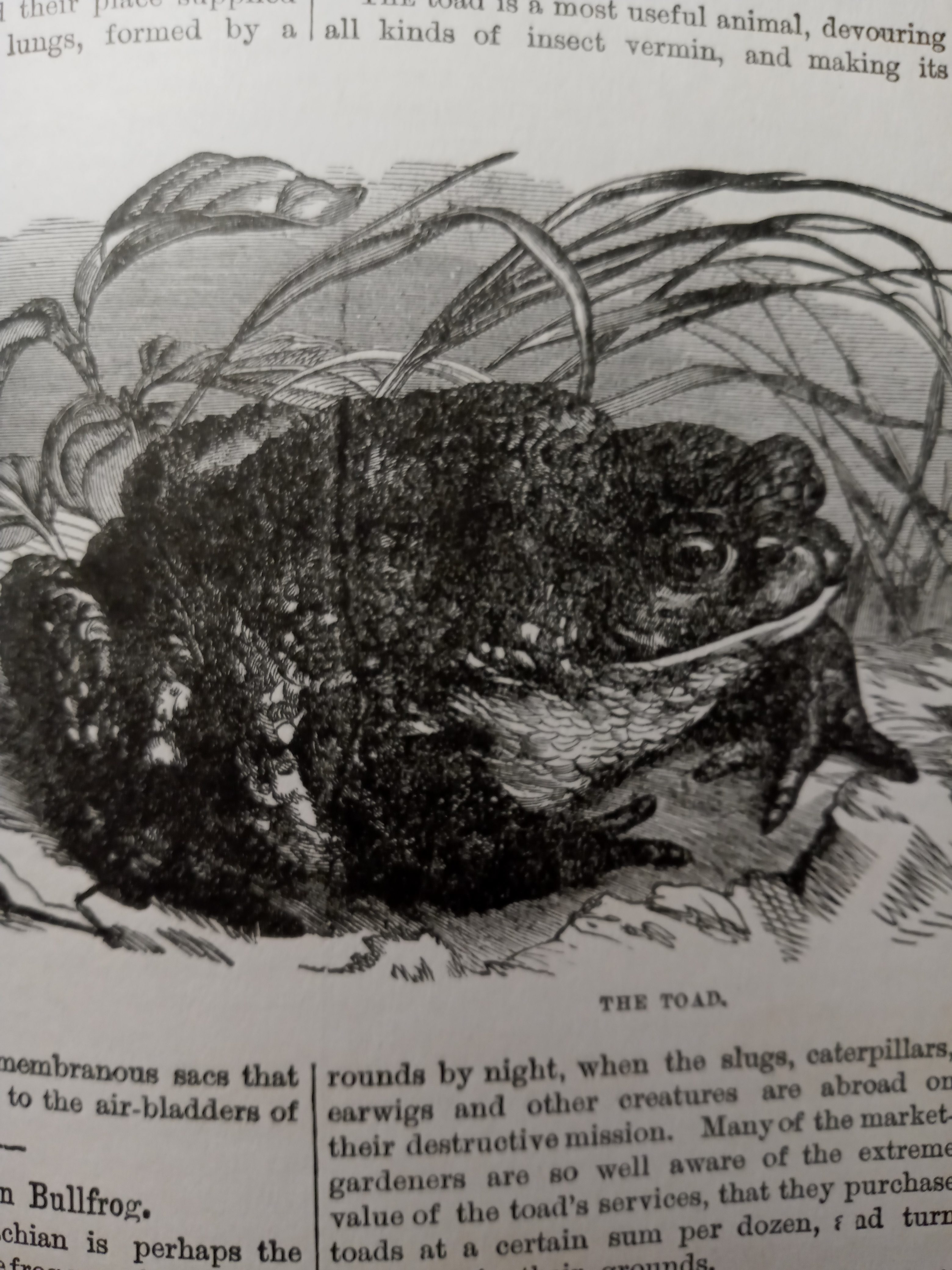

The pond is about knee-deep, and there is no way for the toads who hop into the nursery to make their great escape. So, as we clean the empty pond, the toads are taken back to the tree line and crawl or hop away to their homes. While on the topic, a distinguishing factor between toads and frogs is in their locomotion. Frogs are much more interested in jumping and leaping unless climbing, whereas toads are fairly fond of crawling but will hop from time to time. Another way to tell the difference is in the skin, which tends to be more “warty,” drier, and rougher for toads. This skin is pretty unique for amphibians, and it allows them to retain more moisture, which means they can travel farther away from water sources than frogs.

However, water still plays a vital role in the life of toads as they need it to lay their eggs. Female toads typically lay one or two jelly-like strings with little black dots (the eggs). In about two weeks, these eggs will present tadpoles, although this can happen in a few days in certain circumstances. During their time as tadpoles, they will eat microscopic plant material and algae. Which is why they can be seen swimming in large numbers and having the best day, every day, in the Lily Pond once we turn the water on. The algae bloom and new lilies that kick-start the pond’s ecosystem are equivalent to a tadpole’s Disney World, sans the long lines.

Tadpoles do sport a pair of gills to help them breathe, similar to fish. However, these gills are not as efficient in providing oxygen, so tadpoles will rise to the surface for air once big enough to break the water’s surface. Tadpoles also took swimming in schools from the fish’s playbook on how to avoid predators. Although it is said that tadpoles can be toxic to most animals, so they tend to be left off the menu of would-be diners.

The tadpoles go through metamorphosis over the next sixty days or so, gradually growing limbs, absorbing their tails, and closing their gills. They then leave the water to live a terrestrial life as toads. And this is where the name Amphibian comes from. Its origin is in the Greek word “amphibious,” which translates to “leading a double life” — a life spent pretending to be a fish and eating algae, to a life spent singing in the night for love while also eating an estimated 200 insects NIGHTLY! Toads; the creatures that serenade the summer evenings with love. Toads; the whimsical animals that hop into our childhood imaginations. Toads; the adorable amphibians we incorporate into mainstream media. Toads; an insect-chomping terminator in search of Sarah Connor. So much so are toads bug-eating machines, that one of my sources of toad research states that toads can be brought indoors and let free to help control pests.

Granted, this book was also written in 1888. Times were very different back then. There was no Orkin Man, just a Croaking Toad, which would have been more cost efficient and much more eco-friendly. It goes without saying, please do not release toads in your modern-day house. Now, the toads that I have been lucky enough to encounter for this documentation journey have so far been Eastern American Toads (Anaxyrus americanus).

There are a few ways one can differentiate toad species without a dna kit. First their calls are fairly unique to each species. This is the Eastern American Toad call.

Second, the amount of warts that are encircled on their backs. In the case of Eastern American Toads, they have between one and three warts encircled. Third, the cranial crest and parotoid gland shape and spacing. In Eastern American Toads, the cranial crest does not touch the parotoid gland. This is the gland that secretes the toad’s defense mechanism: bufotoxin. This is a poisonous toxin that helps to keep the toads from being eaten. Not only does it taste bad, but it can make you very sick. This is not to say the toad does not have predators though. Snakes, raccoons, and even other toads may decide the bufotoxin is worth it.

There are other ways we can tell one species of toad apart from another species, but I think this is enough to get you started. That being said, keep in mind that toad species can and do look very similar, so it comes down to checking more boxes in one species versus the other. And even then… they are known to mate with other toad species, and hybrids are common. In autumn, they begin to dig winter homes below the frost line where they go into a state of hibernation, waiting for spring to come. These amazing creatures can live for about two years and often return to their place of birth for mating. As we raise our lineage in our neighborhood parks and are loyal to our ancestral playgrounds, so too are the toads. To me, the toad represents a symbolic key. One of the first keys that open the door to the wonder of the natural world for children. And a key that connects us adults back to our childhood when we see the excitement from our own kids when they discover a toad. “We found at least twenty toads in here, they are everywhere!” the Boy Scout shouted, as the rest of his troop excitedly gathered around to see. The adults looked on with smiles, remembering their first time meeting a toad.

References:

Behler, J. L. and King, F. W., (1979), The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., New York.

Readers Digest, (1991), Nature In America: Your. WaS Guide to Our Country’s Animals, Plants, Landforms and Other Natural Features, The Readers Digeat Association, Inc., New York.

Johnson, T. R., (2000), The Amphibians and Reptiles of Missouri, Missouri Department of Conservation.

Leslie, F. (1888), The Kingdom of Nature And Illustrated Museum of the Animal World, Charles C.Thomlsom Co., Chicago

Leave a comment